Adaptation is the fifth of the five principles of natural selection introduced by Charles Darwin in The Origin of Species. The long-necked giraffe once served as a popular example of adaptation. Darwin explained –

Adaptation is the fifth of the five principles of natural selection introduced by Charles Darwin in The Origin of Species. The long-necked giraffe once served as a popular example of adaptation. Darwin explained –

“The structure of each part of each species, for whatever purpose it may serve, is the sum of many inherited changes, through which the species has passed during its successive adaptations.”

Two twentieth-century contributors, Ernst Mayr and Yuri Filipchenko, however, developed our modern understanding of adaptation in Earth’s biosphere.

V.I.S.T.A.

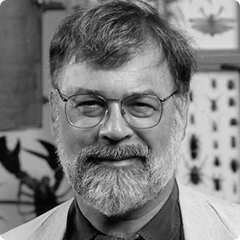

Niles Eldredge (pictured right), of the American Museum of Natural History, introduced the V.I.S.T.A. framework to codify the principles of Darwin’s theory. The five structural principles of natural selection are variation, inheritance, selection, time, and adaptation.

Niles Eldredge (pictured right), of the American Museum of Natural History, introduced the V.I.S.T.A. framework to codify the principles of Darwin’s theory. The five structural principles of natural selection are variation, inheritance, selection, time, and adaptation.

Darwin once argued that adaptation acts as a unifying factor that ultimately leads to the emergence of “new species,” arguing –

“New species have come on the stage slowly and at successive intervals.”

However, our modern understanding of adaptation is a microevolutionary process, not a macroevolutionary process of speciation.

Adaptation-Driven Evolution

Yet, adaptation is not a single process. While variation introduces change, inheritance connects generations, selection filters variation, and time extends intervals; adaptation stems from the culmination of these processes. Darwin (pictured left) explained –

Yet, adaptation is not a single process. While variation introduces change, inheritance connects generations, selection filters variation, and time extends intervals; adaptation stems from the culmination of these processes. Darwin (pictured left) explained –

“Natural selection generally acts with extreme slowness … by accumulating slight, successive, favorable variations.”

Darwin envisioned the adaptive changes of “natural selection” to drive the formation of Earth’s vast biosphere through “descent with modification.” Darwin envisioned –

“From so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”

In essence, adaptations are nature’s configurations driven by Earth’s biospheric contingencies.

Astronomic Biosphere Contingencies

Earth’s biosphere is subject to continuously changing environmental contingencies. Biological adaptations are essential for survival, including responses to astronomical rhythms.

Earth’s biosphere is subject to continuously changing environmental contingencies. Biological adaptations are essential for survival, including responses to astronomical rhythms.

The Earth’s spin and orbital path around the Sun generate seasonal cycles, producing constant, often dramatic swings in temperature, wind, and precipitation.

Simultaneously, the Moon’s rotation around the Earth also causes the flow of Earth’s oceans through alternating spring and neap tides. As a result, the amplitude of these tidal swings can be dramatic, driven by the Moon’s position relative to Earth twice daily.

Planet Biosphere Contingencies

Geological, biological, and anthropogenic contingencies simultaneously threaten the survival of Earth’s biosphere. Evolutionary scientists view these as drivers of natural selection and, ultimately, as the origin of new life forms.

Adaptations emerge from small-scale variation within populations, driven by these environmental contingencies. As a result, the preservation of Earth’s biosphere depends on life’s capacity to adapt. However, while adaptation may explain why biological change occurs – but it does not explain how.

In contemporary biology, adaptation is the emergent fitness advantage arising within populations. The cumulative processes of natural selection are known as microevolution.

Nineteenth-Century Adaptation Concepts

In the Introduction of The Origin of Species, Darwin comments on how his evolution French predecessor, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (pictured left), understood the origin of adaptations, noting –

In the Introduction of The Origin of Species, Darwin comments on how his evolution French predecessor, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (pictured left), understood the origin of adaptations, noting –

“To this latter agency [use and disuse] he seems to attribute all the beautiful adaptations in nature; such as the long neck of the giraffe for browsing on the branches of trees… are now spontaneously generated. Science has not yet proved the truth of this belief.”

While Darwin agreed with Lamarck in principle, he regarded Lamarck’s popular notion of “spontaneous generation” as unscientific. Darwin understood that the scientific framework requires empirically testable observations and measurements. However, Lamarck had none.

By introducing natural selection as the mechanism driving evolution, Darwin opened a new avenue of scientific inquiry. Since adaptations are empirically observable and measurable, natural selection provides a framework for studying evolution scientifically.

However, for Darwin, how Earth’s vast biosphere emerged “from so simple a beginning” is as critical as understanding why.

How, Not Why

Natural selection opened a new avenue, shifting evolutionary studies from ‘why’ to ‘how’. In the introduction to On the Origin of Species, Darwin signals this philosophical shift with a striking prediction –

“The future question for naturalists will be how, for instance, cattle got their horns, and not for what they are used.”

Understanding how nature works is the aim of scientific investigations, a process crystallized in the sixteenth century. Natural selection is understood as the process explaining how evolution works, not why. Viewing the accumulation of “beautiful adaptations” as drivers of the origin, diversity, and survival of Earth’s biosphere, Darwin wrote –

“Hence, the structure of each part of each species, for whatever purpose it may serve, is the sum of many inherited changes, through which the species has passed during its successive adaptations to changed habits [use and disuse] and conditions of life.”

Yet, while there were reasons why new adaptations emerge, explanations for how adaptations develop remained beyond the reach of science.

For good reasons, Darwin did not use the term “evolution” in The Origin of Species. Before Darwin, the concept of evolution was a mere speculation.

Early Evolution Concepts

Early concepts of adaptive-driven evolution were anchored in logic rather than science, beginning with Greek philosophers (Aristotle pictured left) in the sixth century BC. Observable similarities among closely related species lent credence to the idea that Earth’s biosphere emerged through the accumulation of successive adaptations.

Early concepts of adaptive-driven evolution were anchored in logic rather than science, beginning with Greek philosophers (Aristotle pictured left) in the sixth century BC. Observable similarities among closely related species lent credence to the idea that Earth’s biosphere emerged through the accumulation of successive adaptations.

Evolutionary concepts gained popularity among idealists, particularly during the later Age of Enlightenment, including segments of the church. Likewise, natural philosophers integrated reason and empirical observation, advancing the idea that nature drives orderly, progressive biological change.

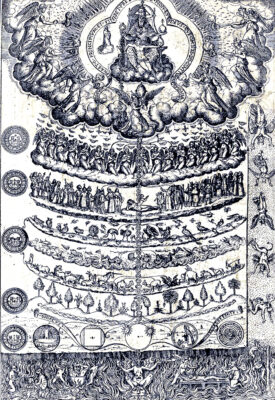

In the sixteenth century, Franciscan friar Didacus Valadés devised a copperplate engraving to illustrate a theistic concept of evolution, entitled the Great Chain of Being (pictured right). Valadés was born in Mexico to a Spanish conquistador father and his Indigenous wife.

In the sixteenth century, Franciscan friar Didacus Valadés devised a copperplate engraving to illustrate a theistic concept of evolution, entitled the Great Chain of Being (pictured right). Valadés was born in Mexico to a Spanish conquistador father and his Indigenous wife.

By the twentieth century, evolution driven by adaptation had become a cultural norm in global media. However, scientific testing would have to wait for the technological advances of the twenty-first century.

Late Nineteenth-Century Reset

By the nineteenth century, evolutionary concepts offered logical constructs for the history of Earth’s biosphere. However, recognizing the stigmatizing issues with antiquated explanations associated with “evolution,”

By the nineteenth century, evolutionary concepts offered logical constructs for the history of Earth’s biosphere. However, recognizing the stigmatizing issues with antiquated explanations associated with “evolution,”

Darwin never used the term in The Origin of Species. However, Darwin did use “evolve” sparingly, including the last sentence of all six editions –

“…from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”

Darwin aimed to scientifically reframe the understanding of evolution, drawing on observable adaptations. In place of the term “evolution,” Darwin used phrases like “descent with modification,” “natural selection,” “struggle for existence,” and “preservation of favored races.”

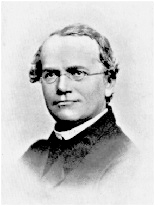

Yet, by the late nineteenth century, the possibility of validating Darwin’s theory scientifically had essentially been eclipsed. Not until the rediscovery of Gregor Mendel’s (pictured right) laws of inheritance early in the twentieth century did scientific interest in Darwin’s theory re-emerge.

Genomic Revolution

Mendel’s landmark 1865 study presentation, Experiments on Plant Hybridization, upended the reigning popular concept of blending inheritance. Studying pea plants, Mendel established that discrete, non-blending traits govern inheritance. Although his findings were published the following year in Proceedings of the Natural History Society of Brünn, they gained little interest at the time.

Mendel’s landmark 1865 study presentation, Experiments on Plant Hybridization, upended the reigning popular concept of blending inheritance. Studying pea plants, Mendel established that discrete, non-blending traits govern inheritance. Although his findings were published the following year in Proceedings of the Natural History Society of Brünn, they gained little interest at the time.

Late-nineteenth-century naturalists eventually came to understand Mendel’s work, which became the foundation of modern genetic inheritance. In contrast to Darwin’s assumptions, Mendel’s particulate model explains how newly acquired adaptations may be transferred from one generation to the next. The breakthrough launched the Genomic Revolution.

Mendel’s predictive framework enabled the mathematical modeling of adaptive changes across generations. This molecular inheritance framework, combined with fossil record data, opened unprecedented opportunities for scientific study of Earth’s biosphere.

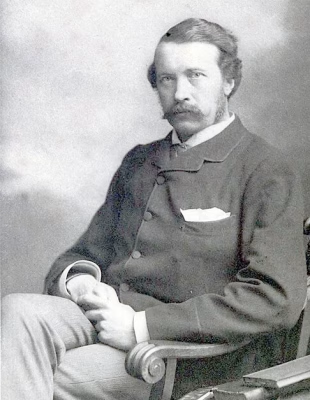

In 1895, with this new inheritance model, George John Romanes (pictured right) re-coined Darwin’s theory as “neo-Darwinism.” The new understanding enabled the testing of Darwin’s “transitional link” concept alongside molecular signatures embedded in living and extinct genomes.

In 1895, with this new inheritance model, George John Romanes (pictured right) re-coined Darwin’s theory as “neo-Darwinism.” The new understanding enabled the testing of Darwin’s “transitional link” concept alongside molecular signatures embedded in living and extinct genomes.

Studies on evolution shifted from interpreting the fossil record to decoding how adaptive traits are molecularly modified and inherited.

Adaptation Evidence Shift

The inclusion of genetic inheritance synchronized with molecular phylogenetic adaptations broadened the scope of evolutionary studies. Evolutionary phylogenetics uses molecular data, including DNA, RNA, and protein sequences, to investigate evidence of successive adaptations in closely related species.

The inclusion of genetic inheritance synchronized with molecular phylogenetic adaptations broadened the scope of evolutionary studies. Evolutionary phylogenetics uses molecular data, including DNA, RNA, and protein sequences, to investigate evidence of successive adaptations in closely related species.

Molecular phylogenetic data are more precise and quantifiable than morphology-based data. The integration of natural selection with Mendelian inheritance provides a testable framework for examining the history of Earth’s biosphere.

Adaptive Modeling

In the 1920s and 1930s, evolutionary scientists Ronald Fisher, Sewall Wright, and J.B.S. Haldane (pictured left) broadened the scope of evolutionary studies. Fisher mathematically linked genetic variation to the rate of adaptive change; Wright pioneered the concept of genetic drift; and Haldane integrated mathematical models with empirical observations.

In the 1920s and 1930s, evolutionary scientists Ronald Fisher, Sewall Wright, and J.B.S. Haldane (pictured left) broadened the scope of evolutionary studies. Fisher mathematically linked genetic variation to the rate of adaptive change; Wright pioneered the concept of genetic drift; and Haldane integrated mathematical models with empirical observations.

By integrating these approaches, new scientific frameworks emerged to investigate adaptive gene-centric models of evolution. The shift unified evolutionary biology under a shared adaptive framework.

However, by the 1940s, paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson began questioning the power of adaptations to drive “The Origin of Species.” While natural selection drives changes within a species, the emergence of a new species from an existing species remained questionable.

Simpson’s concern was widely shared among other evolutionary scientists.

Two Types of Biological Evolution

During the same timeframe, evolutionary scientists struggled with a seeming disconnect between adaptation and speciation. Yuri Filipchenko (pictured left), a Russian entomologist, coined the terms “microevolution” and “macroevolution” in Variabilität und Variation, published in 1927.

During the same timeframe, evolutionary scientists struggled with a seeming disconnect between adaptation and speciation. Yuri Filipchenko (pictured left), a Russian entomologist, coined the terms “microevolution” and “macroevolution” in Variabilität und Variation, published in 1927.

Filipchenko integrated Mendelian genetics into a view of biological evolution as two distinct processes. While supporting Darwin’s small-scale concept of adaptive microevolution, Filipchenko upended Darwin’s adaptive explanation for the origin of new species. In The Origin of Species, Darwin had asserted –

“The theory of natural selection is grounded on the belief that each new variety, and ultimately each new species, is produced.”

Filipchenko toppled Darwin’s concept of “ultimately” extending microevolution to drive the formation of new species, i.e., macroevolution.

Filipchenko viewed microevolution and macroevolution as distinctly different mechanisms. While microevolution is a successive, genetically driven adaptive process, macroevolution is a non-successive, non-adaptive process of speciation.

As the founder of the USSR Academy of Sciences Institute of Genetics, Filipchenko influenced the emerging gene-centric concepts of macroevolution.

Theoretical Shift

Filipchenko, Theodosius Dobzhansky’s first mentor, shifted the focus from Darwin’s concept of successive adaptive changes to gene-centric concepts of macroevolution.

Filipchenko, Theodosius Dobzhansky’s first mentor, shifted the focus from Darwin’s concept of successive adaptive changes to gene-centric concepts of macroevolution.

After Immigrating to the United States in 1927, Dobzhansky’s 1937 publication, Genetics and the Origin of Species, played a significant role in the emergence of the Modern Synthesis.

While adaptive changes within populations proved measurable, scientific measures for the emergence of new species proved problematic. Increasingly, “evolution” was envisioned as two distinct processes independent of successive adaptations.

As the theory of evolution drew increasing interest and scrutiny, evolutionary scientists’ focus on emerging genetic concepts escalated.

Modern Synthesis Theory

Dobzhansky’s radiation-induced fruit fly experiments reinforced the centrality of concepts of genetic variation in evolutionary biology. Enshrined as a mosaic (pictured left) in the halls of biology at the University of Notre Dame, Dohzansky’s phrase encapsulates evolution’s emerging role –

Dobzhansky’s radiation-induced fruit fly experiments reinforced the centrality of concepts of genetic variation in evolutionary biology. Enshrined as a mosaic (pictured left) in the halls of biology at the University of Notre Dame, Dohzansky’s phrase encapsulates evolution’s emerging role –

“Nothing makes sense in biology, except in the light of evolution.”

In 1942, evolutionary biologist Julian Huxley introduced the term “Modern Synthesis” in his book, Evolution: The Modern Synthesis. The same year, Ernst Mayr (pictured right) published Systematics and the Origin of Species. Huxley sought to unify biology within an evolutionary framework, whereas Mayr focused on the evolutionary mechanisms of speciation.

In his publication, Mayr accomplished what Darwin did not: define the term “species.” Known as the Biological Species Concept (BSC), the definition was pivotal for advancing the emerging Modern Synthesis theory of evolution.

Defining species as “reproductive isolation” lineages capable of producing fertile offspring upended the practice of defining species by visible appearances. Mayr’s inheritance-dependent definition of adaptation separated adaptation from speciation, heightening the shift toward a gene-centric view of evolution.

However, studying the shift scientifically requires technical support.

Genomic Revolution

By the mid-twentieth century, the biotechnology equipment continued to expand its capacity to explore the secret drivers of life. Emerging recombinant DNA technologies, which allow genes to be analyzed, cut, spliced, and examined, launched the Genomic Revolution.

By the mid-twentieth century, the biotechnology equipment continued to expand its capacity to explore the secret drivers of life. Emerging recombinant DNA technologies, which allow genes to be analyzed, cut, spliced, and examined, launched the Genomic Revolution.

While the scientific evidence for adaptive-driven microevolution is well established, adaptive-driven macroevolution has not been established at any level.

Biologist Richard Lenski (pictured right) at the University of California, Irvine, designed a study to test a species’ morphological and genetic adaptive limits.

Adaptation Limits

In 1988, Lenski launched the longest-running evolutionary experiment in the history of evolutionary science. The Genomic Revolution enabled Lenski to test key molecular assumptions in assessing the crucial link between microevolution and macroevolution.

In 1988, Lenski launched the longest-running evolutionary experiment in the history of evolutionary science. The Genomic Revolution enabled Lenski to test key molecular assumptions in assessing the crucial link between microevolution and macroevolution.

Coined as the long-term evolution experiment (LTEE), Lenski’s experiment tested the scope of nature’s adaptation processes. Using the bacterium Escherichia coli (pictured right), the experiment has now been running continuously for more than three decades.

The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) has funded Lenski’s project from the outset. The experiment is testing adaptive changes in the 12 original bacterial populations (pictured above) by progressively varying environmental conditions.

Each day, the cell sizes, growth rates, colony morphologies, and genomic sequences are measured and documented. Samples from each population are then preserved for reference and further study.

The experiment is designed to test and link Darwin’s concept of adaptation-related variations to the emergence of new species – the “Origin of Species.”

In Pursuit of How

Answering Darwin’s question of how new species emerge from adaptations has remained beyond the reach of science. The genomic revolution offers the tools to address Darwin’s lingering “how” question scientifically.

The problem is not the lack of new species to study. Over recent decades, the rate of new species discoveries has exploded, now averaging an estimated 10,000 per year. And, despite the estimated 3-100 million eukaryotic species currently living on Earth’s biosphere, the lack of species to study is not the problem, either.

The absence of empirical evidence for adaptation-driven speciation calls into question whether adaptations can, in fact, drive speciation. Lenski’s experiment tests whether Darwin’s theory of adaptation-to-divergence-to-speciation is “how” evolution works.

Over decades of experimentation, Lenski has observed thousands of adaptively driven novelties emerge. However, none of these changes have met Mayr’s species criteria.

Coupled with the absence of empirical macroevolutionary observations published in peer-reviewed journals, efforts to revise the Modern Synthesis became increasingly inevitable.

Beyond Molecular Adaptations

Philosopher Massimo Pigliucci (pictured left) and evolutionary biologist Gerd B. Müller (pictured left) hosted an invitation-only conference to address issues in the Modern Synthesis. Dubbed “The Altenberg 16” in recognition of its 16 attendees, the July 2008 conference convened in Altenberg, Austria.

Philosopher Massimo Pigliucci (pictured left) and evolutionary biologist Gerd B. Müller (pictured left) hosted an invitation-only conference to address issues in the Modern Synthesis. Dubbed “The Altenberg 16” in recognition of its 16 attendees, the July 2008 conference convened in Altenberg, Austria.

At the Konrad Lorenz Institute for Evolution (KLI), conference attendees discussed extending the mechanisms of Modern Synthesis beyond adaptations. In anticipation of heated press coverage, the press was barred from the meeting.

A report from the conference was never published, and the events remained secret for two years.

Evolution, The Extended Synthesis

In 2010, Pigliucci and Müller, as editors and authors, published Evolution: The Extended Synthesis by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The 495-page volume, comprising 17 chapters in 6 sections, was written by “The Altenberg-16” participants.

In 2010, Pigliucci and Müller, as editors and authors, published Evolution: The Extended Synthesis by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The 495-page volume, comprising 17 chapters in 6 sections, was written by “The Altenberg-16” participants.

The attendees’ aim, as explained in the Preface, was to address Darwin’s infamous how question beyond the limits of Modern Synthesis, noting –

“This is a propitious time to engage the scientific community in a vast interdisciplinary effort to further our understanding of how life evolves. An extended evolutionary framework will be key for this endeavor.”

Pigliucci and Müller organized the papers from the attendees into these seven sections: Variation and Selection, Evolving Genomes, Inheritance and Replication, Evolutionary Developmental Biology, Macroevolution and Evolvability, and Philosophical Dimensions.

Adaptation’s Role

Notably, none of the sections focused on the role of adaptations. However, in the Philosophical Dimensions section, written by Werner Callebaut (pictured right) of KLI, it was concluded –

“It should not be thought that the Darwinian Revolution is over.”

The search to understand how nature produces species remained unknown at the time. Callebaut entitled his chapter “The Dialects of Dis/Unity in the Evolutionary Synthesis and Its Extensions,” which opened with the following sentence –

“The thesis of my contribution is that the evolution of evolutionary thinking since the making of the Modern Synthesis has been characterized by simultaneous unifying and disunifying tendencies, with no end in sight.”

Contrary to Pigliucci and Müller’s goals, the development of an extended evolutionary framework never materialized. A consensus on the role of adaptations within the cohesive extended evolutionary synthesis has never developed to account for macroevolution.

The Royal Society Referendum

In 2016, the Royal Society issued a call to renew efforts to revisit extending the Modern Synthesis theory of evolution’s dominant paradigm, noting –

In 2016, the Royal Society issued a call to renew efforts to revisit extending the Modern Synthesis theory of evolution’s dominant paradigm, noting –

“Developments in evolutionary biology and adjacent fields have produced calls for revision of the standard theory of evolution, although the issues involved remain hotly contested.”

The three-day event was titled “New Trends in Evolutionary Biology: Biological, Philosophical, and Social Science Perspectives.” Several hundred attended the meetings.

Epigenetics, embryological plasticity, and multi-level systems concepts were discussed as potential mechanisms for extending Modern Synthesis. However, the Society did not reach consensus on how to resolve the deadlock over the link between microevolution and macroevolution.

Consequently, the meeting underscored the lack of a scientifically valid framework in evolutionary biology to account for the “Origin of Species.” The role of adaptation as a driver of macroevolution seemed inevitable.

Consequently, the meeting underscored the lack of a scientifically valid framework in evolutionary biology to account for the “Origin of Species.” The role of adaptation as a driver of macroevolution seemed inevitable.

Lenski was not a participant in the Altenberg or Royal Society meetings.

Decades of Experimental Evolution

Before these two referendum conferences, Lenski had published dozens of significant, ongoing results from the LTEE. The publications documented fitness trajectories, increases in cell size, evolution of mutation rates, parallel versus divergent outcomes, and genomic changes.

Because of their high reproductive rates relative to humans, microbes are ideal models for evolutionary studies. Evolution proceeds by generations rather than clock time; a decade of microbial adaptations corresponds to millions of years in humans.

As of 2025, Lenski’s experiment had studied over 80,000 generations of E. coli, equivalent to nearly 2 million years of human existence. The duration of Lenski’s adaptation experiment is unparalleled in the evolutionary sciences.

Lenski’s Findings

Over nearly 30 years of study, Lenski documented an accumulation of a range of adaptive changes across the 12 E. coli populations. These adaptive changes include shifts in energy utilization from glucose to citrate, genetic mutations, and the emergence of novel traits.

Over nearly 30 years of study, Lenski documented an accumulation of a range of adaptive changes across the 12 E. coli populations. These adaptive changes include shifts in energy utilization from glucose to citrate, genetic mutations, and the emergence of novel traits.

Despite these changes, all 12 original E. coli lineages remained E. coli; no lineage met Mayr’s definition of a new species. Lenski’s observations remained consistent, beginning with his first publication in 1991, noting –

“These results, taken as a whole, are consistent with theoretical expectations that do not invoke divergence (speciation).”

Lenski’s LTEE experiment demonstrates that adaptations emerge within a species (microevolution) in association with shifting environmental contingencies. The universal finding of adaptation within each species functions seamlessly within each species inherent design.

Adaptation Limitations

Adaptation is a conservation process, rather than a creative engine. An accumulation of adaptations once thought to bridge the gap between microevolution and macroevolution has never been observed.

Adaptation is not scientifically validated as a mechanism for transforming a species into a new species, as Darwin once argued. Modern adaptation studies have upended assumptions that antimicrobial resistance is illustrative of how new species emerge.

Twenty-first-century adaptation studies have upended long-held assumptions about adaptive-driven macroevolution, including popular giraffe assumptions.

The Giraffe Lesson

Lamarck and Darwin assumed that long necks evolved to give giraffes a competitive advantage by allowing them to reach leaves on tall trees. However, neither had any empirical supportive observations.

Lamarck and Darwin assumed that long necks evolved to give giraffes a competitive advantage by allowing them to reach leaves on tall trees. However, neither had any empirical supportive observations.

During the dry season, biologist Robert Simmons of Uppsala University studied wild giraffes’ feeding in Africa through direct field observations. In “Winning by a Neck,” published by The American Naturalist. Simmons reported –

“We find that during the dry season (when feeding competition should be the most intense) giraffes generally feed on low shrubs, not tall trees… Each result suggests that long necks did not evolve specifically for feeding at higher levels… We thus find little critical support for the Darwinian feeding competition idea.”

Although Lamarck and Darwin had a logical argument, the scientific evidence undermined it.

Genesis

French chemist and microbiologist, Louis Pasteur, discoverer of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization, encapsulates the challenges to understand nature –

French chemist and microbiologist, Louis Pasteur, discoverer of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization, encapsulates the challenges to understand nature –

“A bit of science distances one from God, but much science nears one to Him… The more I study nature, the more I stand amazed at the work of the Creator.”

The emergence of new species through adaptation-driven macroevolutionary processes is not a scientifically valid theory.

Evolution beyond adaptation is a theory in crisis.

Adaptation, Fifth Principle of Natural Selection is a Theory and Consensus article.

More

Natural selection’s five principles, coined as an acronym and causal sequence, are V.I.S.T.A –

Darwin Then and Now is an educational resource on the intersection of evolution and science, highlighting the ongoing challenges to the theory of evolution.

Move On

Explore how to understand twenty-first-century concepts of evolution further using the following links –

-

- The Understanding Evolution category showcases how varying historical study approaches to evolution have led to varying conclusions. Subcategories include –

- Studying Evolution explains how key evolution terms and concepts have changed since the 1958 publication of The Origin of Species.

- What is Science explains Charles Darwin’s approach to science and how modern science approaches can be applied for different investigative purposes.

- Evolution and Science feature study articles on how scientific evidence influences the current understanding of evolution.

- Theory and Consensus feature articles on the historical timelines of the theory and Natural Selection.

- The Biography of Charles Darwin category showcases relevant aspects of his life.

- The Glossary defines terms used in studying the theory of biological evolution.

- The Understanding Evolution category showcases how varying historical study approaches to evolution have led to varying conclusions. Subcategories include –