Each fossil record discovery has a unique story, and the Archaeoraptor matter is undoubtedly no exception. In November 1999, a feature article in National Geographic titled “Feathers for T. Rex? New Birdlike Fossils Are Missing Links In Dinosaur Evolution” turned out to be one of the most spectacular debacles in the history of paleontology, rivaling the Piltdown Man saga. The article alleged –

Each fossil record discovery has a unique story, and the Archaeoraptor matter is undoubtedly no exception. In November 1999, a feature article in National Geographic titled “Feathers for T. Rex? New Birdlike Fossils Are Missing Links In Dinosaur Evolution” turned out to be one of the most spectacular debacles in the history of paleontology, rivaling the Piltdown Man saga. The article alleged –

“A true missing link in the complex chain that connects dinosaurs to birds.”

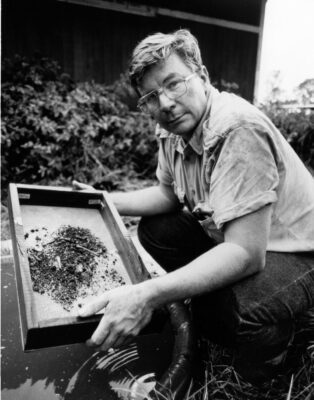

Discovered in the northeastern Liaoning Province of China in 1997 by farmers (pictured left), the fossil appeared to have a bird’s body with a small, terrestrial dinosaur’s teeth and tail. The name given to the fossil, Archaeoraptor liaoningensis, is in recognition of its discovery site.

In Latin, “archaeo” means “ancient,” and “raptor” means “plunderer.” Science journalist Christopher Sloan, a four-time award winner of the National Science Teachers Association, authored the National Geographic magazine article. The fossil demonstrated a long, bony tail like that of dinosaurs, with specialized shoulders and chest-like birds. The Archaeoraptor matter pointed to a “true missing link” between birds and terrestrial theropod dinosaurs.

The Back-Story

In 1997, farmers digging in the shale pits unearthed a rare toothed bird, complete with feathers, broken into pieces. Someone found nearby a similar-sized finding with a feathered tail and legs broken apart. Knowing that complete fossils sell better, the discoverers glued the pieces together and sold the composite to an anonymous dealer in June 1998.

In 1997, farmers digging in the shale pits unearthed a rare toothed bird, complete with feathers, broken into pieces. Someone found nearby a similar-sized finding with a feathered tail and legs broken apart. Knowing that complete fossils sell better, the discoverers glued the pieces together and sold the composite to an anonymous dealer in June 1998.

At the 1998 fall meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Utah, rumors circulated about a remarkable new primitive bird fossil still in private hands. A few months later, at a gem and mineral show in Tucson, Arizona, Stephen A. Czerkas (pictured right), director of The Dinosaur Museum in Blanding, Utah, purchased the Archaeoraptor fossil from an unknown agent for $80,000.

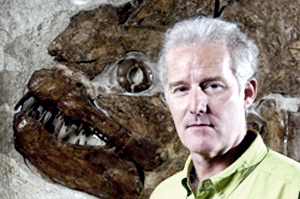

Looking for advice, Czerkas contacted Philip J. Currie (pictured left), a Canadian paleontologist. Recognizing the apparent significance of the fossil and the legal challenges, Currie contacted the National Geographic Society.

Looking for advice, Czerkas contacted Philip J. Currie (pictured left), a Canadian paleontologist. Recognizing the apparent significance of the fossil and the legal challenges, Currie contacted the National Geographic Society.

Since China’s penalty for selling a fossil without government approval is execution, Sloan convinced Czerkas to return the fossil to China immediately after publication in National Geographic. Czerkas agreed.

To begin the collaboration with China, Czerkas and Currie contacted the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing.

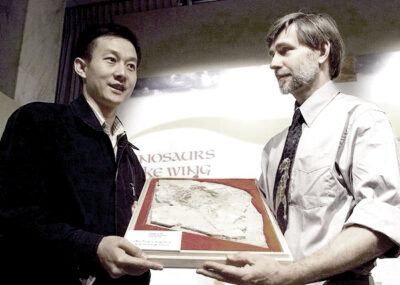

With a collaborative plan developed, National Geographic arranged to fly Chinese paleontologist Xu Xing (pictured right) from China to Utah to join the Archaeoraptor team a few months later.

Lewis M Simons, a veteran investigative Associated Press (AP) reporter working with National Geographic, traveled to China for an on-site investigation. Simons confirmed that –

“The story began on an oven-hot day late in July 1997, when a farmer [was] digging in a shale pit in Xiasanjiazi.”

Fossil hunting in China is a nefariously profitable business for farmers and Communist Party officials. As Simons explains –

“While authorities in Beijing insist that no fossils may leave the country legally, the reality is that huge quantities are taken out, most through the expediency of bribing local officials.”

CT Examination

During the Archaeoraptor matter initial visual examination in March 1999, it seemed likely that the specimen was a composite of two different stone slab fragments. Since the connection between the body section and the tail and leg section seemed ambiguous, the team sent the fossil to Timothy Rowe (pictured right) at the University of Texas for an X-ray examination.

During the Archaeoraptor matter initial visual examination in March 1999, it seemed likely that the specimen was a composite of two different stone slab fragments. Since the connection between the body section and the tail and leg section seemed ambiguous, the team sent the fossil to Timothy Rowe (pictured right) at the University of Texas for an X-ray examination.

In July, Rowe, a paleontologist specializing in the vertebrate skeleton using digital technologies, scanned the specimen using high-resolution computed tomography (CT). As suspected, Rowe concluded that the specimen was a composite of two slab fragments.

According to Rowe, the smaller bottom fragments contained the tail and the lower legs, while the larger upper fragment contained the fossilized wings, thorax, and head fossil fragments.

On August 2, Rowe informed the Czerkases that there was a possibility that the whole thing was a fraud. Czerkas pressured the team members to keep the test results private during subsequent discussions, leaving the Archaeoraptor matter National Geographic blind-sided.

Rush to Publish

Undeterred by the evidence, in August, the Archaeoraptor team, including Czerkas, Currie, Rowe, and Xu, submitted a paper on the specimen from China entitled “A New Toothed Bird With a Dromaeosaur-like Tail” to the British journal Nature.

Undeterred by the evidence, in August, the Archaeoraptor team, including Czerkas, Currie, Rowe, and Xu, submitted a paper on the specimen from China entitled “A New Toothed Bird With a Dromaeosaur-like Tail” to the British journal Nature.

As the paper was en route to London, Henry Gee (pictured right), senior editor of Nature, emailed a furious message to Barbara Moffet in the National Geographic Society’s public affairs office.

Gee, apprised of the National Geographic plan, explained to Moffett that a peer review was not possible before the Society’s scheduled September publication date. Gee copied Rowe, Currie, and Xu, but not the Czerkases.

The following day, Rowe responded in an email to Gee, stating he had been “sucked into” the project with “no idea of just how poorly the entire enterprise” had been managed. Rowe explained further –

“The publicity circus that the Czerkas’ have tried to orchestrate with [the National Geographic Society] has been driving way too much of the project, and that I just hope that it hasn’t now completely [expletive] the scientific side.”

Still, Rowe explained that Archaeoraptor is “a critical specimen,” noting that he “signed on to this drowning party–and why I guess I’ll put in a few more hours to try to straighten out the whole mess.”

Within the week, Nature rejected the paper because of National Geographic’s time constraint. In an email to Czerkas, Gee noted –

“We would not be prepared to consider this manuscript for possible publication in Nature.”

The Archaeoraptor team quickly shifted gears. With a few modifications, they submitted the paper to the American journal of Science.

Two reviewers noted that “the specimen was smuggled out of China and illegally purchased.” More damaging, the reviewers reported that the fossil had been “doctored” in China “to enhance its value.” Science rejected the paper, too, arguing for more proof of Archaeoraptor’s birdlike qualities.

Still undeterred, in September, Currie sent Kevin Aulenback, a fossil technician, to Czerkas’ Dinosaur Museum in Utah to “prep” the specimen for public exhibit. However, on the way back to Alberta, Aulenback emailed Currie to state that “Archaeoraptor” was –

“A composite specimen of at least three specimens…with a maximum…of five…separate specimens.”

A published scientific report on Archaeoraptor matter never appeared in any peer-reviewed journal.

On October 15, 1999, National Geographic published “Feathers for T. Rex?” for the November issue, written by Christopher P. Sloan, a National Geographic art editor, as initially planned. The Archaeoraptor Team blindsided Sloan, secretly hiding known problems with the fossil and Nature and Science’s rejections.

As the “long-sought-after key to the mysteries of evolution,” Sloan blindly explained the significance of the fossil –

“… a true missing link in the complex chain that connects dinosaurs to birds… a missing link between terrestrial dinosaurs and birds that could fly.”

During the same month, at the October meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Denver, Rowe presented a paper on the fossil CT scanning. Many scientists were highly critical of Rowe and the National Geographic article. As Rowe, conflictingly, explained to Gee in an email –

“I found myself as an author of a paper returned to us, saying the specimen had been doctored. I take exception to that, but now we have a tool to study it.”

Media Fascination

Fascinated by the implications, the fossil emerged as a superstar. The National Geographic Society held a press conference to display the fossil at its Washington, DC headquarters. The Society produced a media series entitled “Dinosaurs Take Wing” for their Explorer channel, which played on CNBC.

The New York Times, in the article entitled “Scientists Say Fossils From China Prove Dinosaur-to-Bird Link,” announced –

“Indeed, the scientists and their allies contend that the mystery of bird origins has at last been solved and that the close dinosaur-bird link is now beyond debate.”

Fascination To Frustration

The fascination soon turned to frustration, however. Just as the story was gaining international attention, questions about the fossil started taking flight, leaving National Geographic suddenly embroiled in one of the hottest scientific controversies in decades.

In an open letter published on November 1, 1999, Storrs L. Olson (pictured left), a career curator of birds at the Smithsonian Institution, slammed the Archaeoraptor matter –

In an open letter published on November 1, 1999, Storrs L. Olson (pictured left), a career curator of birds at the Smithsonian Institution, slammed the Archaeoraptor matter –

“The hype about feathered dinosaurs in the exhibit currently on display at the National Geographic Society… makes the spurious claim that there is strong evidence that a wide variety of carnivorous dinosaurs had feathers… all of which is simply imaginary and has no place outside of science fiction.”

In the words of Olson, the claims about the Chinese fossil reached –

“An all-time low for engaging in sensationalistic, unsubstantiated, tabloid journalism.”

In December, Xing emailed his co-authors and Sloan to say –

“I am really sorry to tell you bad news!”

A contact in Liaoning showed Xing the counter slab of the extracted Archaeoraptor tail. At the site, Xing found a tiny dromaeosaur fossil to study in his Beijing laboratory. In the laboratory, Xing demonstrated that the yellow iron oxide stain of the dromaeosaur tail impression perfectly mirrored the piece glued into the contrived “Archaeoraptor” fossil. Xing concluded –

“I am 100% sure… we have to admit that Archaeoraptor is a faked specimen.”

National Geographic found itself in an unenviable position. Blaming the fossil fiasco on “zealous scientists,” Olson opined that National Geographic had become “proselytizers of the faith” advancing “scientific hoaxes.” In the words of Olson, they were –

“The paleontological equivalent of cold fusion.”

In February, National Geographic News issued a press release stating that the “Archaeoraptor” fossil might be a fake and that an internal investigation had begun.

The following month, in the March 2000 issue, National Geographic published a letter to the editor from Xing, the Chinese scientist on the Archaeoraptor team, who conceded –

“After observing a new, feathered dromaeosaur specimen … [t]hough I do not want to believe it, Archaeoraptor appears to be composed of a dromaeosaur tail and a bird body.”

The Associated Press [AP] was the first news media to cover the fossil fiasco in the report entitled “Nat’ l Geographic Confirms Mistake,” published on April 7, 2000, written by science writer Randolph E Schmid. As Schmid explained –

“Six months after proclaiming a newly discovered fossil to be a possible link between dinosaurs and birds, the National Geographic Society has confirmed that the find is really a composite of at least two different animals.”

In June 2000, the forged composite from different species was returned to the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (pictured right) in Beijing, China.

After nearly a year of investigation, in October 2000, National Geographic finally published a five-page article written by AP reporter Lewis M Simons describing how the hoax evolved step by step. Rather than a “true missing link,” Simons explains in the article “Archaeoraptor Fossil Trail” –

“To some prominent paleontologists who saw it, though, the little skeleton was a long-sought key to a mystery of evolution. To others…, it was a cheap hoax. And to Bill Allen, Editor of NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC, it was a giant headache.”

The following year, the paper entitled “The Archaeoraptor Forgery,” written by Timothy Rowe, Richard A. Ketcham, Cambria Denison, Matthew Colbert, Xing Xu, and Philip J. Currie, was published in the journal Nature in March 2001. To close the Archaeoraptor matter, Rowe concedes –

“The Archaeoraptor fossil was announced as a ‘missing link’ and purported to be possibly the best evidence since Archaeopteryx that birds did, in fact, evolve from certain types of carnivorous dinosaurs… But Archaeoraptor was revealed to be a forgery in which bones of a primitive bird and a non-flying dromaeosaurid dinosaur had been combined.”

Using high-resolution X-ray CT, Rowe reported that the fossil was a fabricated composite of several species – intensifying Darwin’s dilemma.

The Archaeoraptor matter illustrates what happens when studies violate basic scientific principles, as did Darwin. In a letter to J. Scott in 1863, Darwin advised –

“I would suggest to you the advantage … let the theory guide your observations.”

Genesis

The origin of species is compatible with the Genesis account written by Moses. Nicholas Copernicus (1473-1543) (pictured left), the Renaissance mathematician and astronomer by refusing to let “the theory guide your observations,” upended the once widely accepted geocentric model of the universe. Today, Copernicus is known as the founder of modern astronomy.

The origin of species is compatible with the Genesis account written by Moses. Nicholas Copernicus (1473-1543) (pictured left), the Renaissance mathematician and astronomer by refusing to let “the theory guide your observations,” upended the once widely accepted geocentric model of the universe. Today, Copernicus is known as the founder of modern astronomy.

As a principle of Scientific Revolution, Copernicus notes –

“The mechanisms of the universe, wrought for us by a supremely good and orderly Creator… the system best and most orderly artist of all framed for our sake.”

Evidence for common ancestry and transitional links underscores why the theory of evolution remains speculative but not scientifically valid.

Archaeoraptor Matter is a Fossil Record article.

Darwin Then and Now is an educational resource on the intersection of evolution and science, highlighting the ongoing challenges to the theory of evolution.

Move On

Explore how to understand twenty-first-century concepts of evolution further using the following links –

-

- The Understanding Evolution category showcases how varying historical study approaches to evolution have led to varying conclusions. Subcategories include –

- Studying Evolution explains how key evolution terms and concepts have changed since the 1958 publication of The Origin of Species.

- What is Science explains Charles Darwin’s approach to science and how modern science approaches can be applied for different investigative purposes.

- Evolution and Science feature study articles on how scientific evidence influences the current understanding of evolution.

- Theory and Consensus feature articles on the historical timelines of the theory and Natural Selection.

- The Biography of Charles Darwin category showcases relevant aspects of his life.

- The Glossary defines terms used in studying the theory of biological evolution.

- The Understanding Evolution category showcases how varying historical study approaches to evolution have led to varying conclusions. Subcategories include –

2021 Update

National Geographic Investigation

National Geographic commissioned journalist Lewis M Simons to investigate the Archaeoraptor matter. According to Simons, the matter was –

“A tale of misguided secrecy and misplaced confidence, of rampant egos clashing, self-aggrandizement, wishful thinking, naive assumptions, human error, stubbornness, manipulation, backbiting, lying, corruption, and, most of all, abysmal communication.”

Stephen Czerkas

Czerkas (1951-2015), best known as a paleo-artist, began his career sculpting dinosaurs for the motion picture industry. Without any degree in science, Czerkas was director and co-founder of The Dinosaur Museum in Utah.

Although Czerkas eventually acknowledged that the Archaeoraptor was a composite, he refused all interview requests. According to Rex Dalton, writing for the journal Nature in April 2010,

“Czerkas did not explain the origins of either specimen or describe any scientific exchange with Chinese institutes.”

Phil Currie

Currie later described his involvement in this scandal as –

“The greatest mistake of my life.”

Archaeoraptor Location

A record of the Archaeoraptor disposition has never been published. The picture of the specimen was allegedly taken specimen on display at the Paleozoological Museum of China in 2019.

Fake Fossil Epidemic

The Science (2010) journal article “Altering the Past: China’s Faked Fossils Problem” explains Peking University paleontologist Jiang Da-yong –

“‘ The fake fossil problem has become very, very serious.”‘

In the same article, Li estimates that more than 80% of marine reptile specimens now on display in Chinese museums have been “altered or artificially combined to varying degrees.”

Science writer John Pickrell, in the Scientific American (2014) journal article “How Fake Fossils Pervert Paleontology, A nebulous trade in forged and illegal fossils is an ever-growing headache for paleontologists,” noted –

“An investigative report published in Science in 2010 revealed that as many as 80 percent of marine reptile fossils on display in Chinese museums had been altered or manipulated.”

Managing the Fake Fossil Epidemic

To ensure credibility, paleontologists should develop a rating process and system to distinguish between fake and genuine fossils.

Disappointingly, no science organization has not developed a process to test and validate the fossil’s authenticity scientifically.

Authenticity is crucial, especially for fossils thought to be transitional – as in the Archaeoraptor matter.

Until then, a fossil’s genuine authenticity must be suspect if not proven to be an unchanged specimen.