by Richard William Nelson | Apr 2, 2015

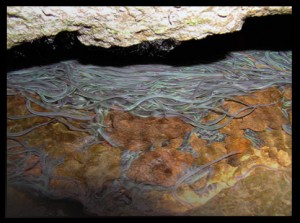

Microbes, once thought to be life’s simplest forms, are now known to use complex, synchronized genetic processing as a defensive system against foreign invading microorganisms.

Microbes, once thought to be life’s simplest forms, are now known to use complex, synchronized genetic processing as a defensive system against foreign invading microorganisms.

As a previously unknown and unrecognized genetic mechanism, CRISPR challenges the tenets of evolution. This microbial defense process, now known as CRISPR, further undermines natural selection’s fundamental principle of early life spontaneously emerging from simple processes.

In The Origin of Species, Charles Darwin envisioned life starting “from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful.” CRISPR presents a new challenge to current theories of evolution, including Darwinism, neo-Darwinism, and the Modern Synthesis theory of evolution.

Continue Reading

by Richard William Nelson | Mar 5, 2015

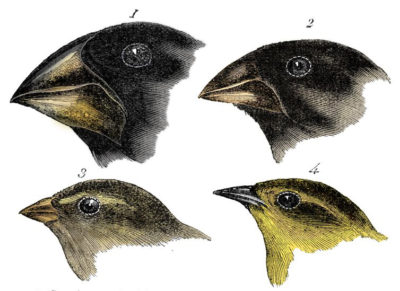

The finches Charles Darwin encountered on the Galapagos Islands have served as one of the most enduring examples of evolution throughout the twentieth century.

The finches Charles Darwin encountered on the Galapagos Islands have served as one of the most enduring examples of evolution throughout the twentieth century.

As Darwin explains in The Origin of Species, “one [finch] species had been taken and modified [changed] for different ends” – the essence of natural selection.

However, in the nineteenth century. The technology to scientifically validate these changes in the genetics of Darwin’s finches was inconceivable.

Continue Reading

by Richard William Nelson | Jan 9, 2015

The genetic code is the universal language of life, from the first microbe to man. Searching for the origins of the first genetic code mystery, however, is akin to deciphering the evolution of life.

The genetic code is the universal language of life, from the first microbe to man. Searching for the origins of the first genetic code mystery, however, is akin to deciphering the evolution of life.

Over the past two years, the research team of Bojan Žagrović (pictured) at the Max F. Perutz Laboratories of the University of Vienna has been searching for a natural mechanism driving the genesis of the original genetic code − a longstanding challenge of the evolution industry.

Since the interactions between genetic material (nucleobases, DNA, and mRNA) and amino acids produce the workhorse molecules of life–proteins, Žagrović’s research team has been focusing on understanding what might have been the initial natural physicochemical mechanisms producing the original genetic code.

Continue Reading

by Richard William Nelson | Nov 28, 2014

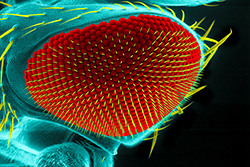

Charles Darwin‘s fascination with insects began early in life. While studying at Cambridge University, his interest continued with earnestness, as he sent James Francis Stephens, his professor of entomology (insects), specimens and descriptions of the critters.

At the time, discussing the evolution of insect genetics would have been as relevant as discussing moon landings. Just months before setting sail on the HMS Beagle in 1831, Stevens published his recognition of Darwin’s work on insects (pictured right) in his widely popular Illustrations of British Entomology.

Continue Reading

by Richard William Nelson | Nov 4, 2014

The European eel illustrates exactly why Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution has continued to be on the wrong side of science. Darwin once argued that.

The European eel illustrates exactly why Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution has continued to be on the wrong side of science. Darwin once argued that.

“By the theory of natural selection, all living species have been connected… So that the number of intermediate and transitional links, between all living and extinct species, must have been inconceivably great.”

Since the publication of The Origin of Species in 1859, Darwin’s “inconceivably great” number of evolutionary transitional links in the fossil record over the past 150 years remains missing despite the vast discovery of fossils.

Continue Reading

Microbes, once thought to be life’s simplest forms, are now known to use complex, synchronized genetic processing as a defensive system against foreign invading microorganisms.

Microbes, once thought to be life’s simplest forms, are now known to use complex, synchronized genetic processing as a defensive system against foreign invading microorganisms.

The

The

The

The