Andrew J. Wendruff and Mark V. H. Wilson, of the University of Alberta, added a new dimension to the ongoing coelacanth saga this week in the paper “A fork-tailed coelacanth, Rebellatrix divaricerca,” published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Andrew J. Wendruff and Mark V. H. Wilson, of the University of Alberta, added a new dimension to the ongoing coelacanth saga this week in the paper “A fork-tailed coelacanth, Rebellatrix divaricerca,” published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

In the paper, Wendruff and Wilson present a newly discovered coelacanth species found surprisingly on the rocky slopes of the Canadian Rockies, British Columbia. The species named Rebellatrix divaricerca means “rebel coelacanth (with a) forked tail.” Far different from today’s Indian Ocean coelacanths, these ancient rebel fast-swimming predators further undermine attempts to develop a cohesive coelacanth saga.

Early Coelacanth Saga

While the discovery of the first coelacanth fossil discovered is currently missing from the history of science, in the aftermath of the naming of the first fossil by Swiss biologist and geologist Louis Agassiz (pictured right) in 1839, however, the coelacanth saga was launched into a pivotal role in the history of evolution.

Emigrating to America in 1847, Agassiz was appointed professor of zoology and geology at Harvard University, later founding the university’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. Given the leg-like structures located in the pelvic area, the coelacanth seemed to exemplify a transitional species between fish and tetrapods – four-limbed vertebrates. Agazzi suggested the evidence points to –

“A correspondence between the succession of Fishes [evolution of fishes] in geological times.”

Charles Darwin agreed. In the first edition of The Origin of Species, Darwin notes –

“This doctrine of Agassiz accords well with the theory of natural selection.”

Agassiz named the fossil the “Coelacanth,” meaning “hollow space,” based on the hollow spines of the backbone. In Greek, “coel” means space, and” acanthus” means the spine.

As presumably an interim fish swimmer transitioning into a terrestrial walker, the coelacanth became popularly known as one of Darwin’s highly prized “missing transitional links.” With his beautifully illustrated book, the Poissons Fossiles (Fossil Fish), published in 1839, Agassiz provided the first descriptive account of the coelacanth.

Biology textbooks throughout the early twentieth century widely portrayed Agassiz’s coelacanth as scientific evidence supporting Darwin’s theory of evolution

Coelacanth Saga Transition

Starting in 1938, however, to the chagrin of biology textbook producers, the once-popular coelacanth storyline quickly transitioned into a coelacanth saga dilemma.

At the opening of the Chalumna River flowing into the Indian Ocean, the netting of a freakishly unknown creature – “a five-foot-long, a pale mauvy blue with faint flecks of whitish spots” – caught the immediate attention of Captain Hendrick Goosen’s crew while returning to East London, South Africa. The date was December 23, 1938.

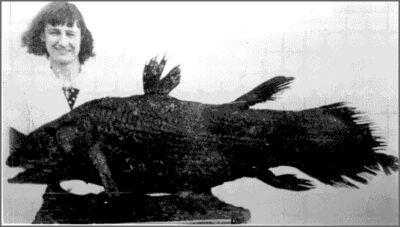

Marjorie Latimer (pictured left), a local curator, was summoned to examine the mysterious catch on the returning fishing trawler. On the deck, Latimer was puzzled by the bizarre – “four limb-like fins and a strange puppy dog tail.”

Without finding a comparative description of the creature anywhere in her library, Latimer mailed ichthyologist J. L. B. Smith at Rhodes University the story and a sketch of the fish. Known only from Latimer’s information, Smith cabled back –

“MOST IMPORTANT PRESERVE SKELETON AND GILLS = FISH DESCRIBED

In honor of Marjorie Latimer and river location, Smith named the puzzlingly fish Latimeria chalumnae.

At one-hundred and twenty pounds, this good-sized presumed “transitional link” was especially bizarre since biology textbooks had dated the fish’s extinction 66 million years earlier. The discovery was considered one of the most notable “living fossil” zoological finds of the twentieth century.

The territorial range of the coelacanth is now known to extend from South Africa to Indonesia, typically at a depth of one thousand feet or more.

Latest Coelacanth Saga

Science 2.0 in the article “Rebellatrix: Ancient Canadian Killer Coelacanth,” Wendruff and Wilson reports –

“Newly discovered extinct coelacanth is causing more waves because of a tuna-like forked tail, meaning it was probably a fast-moving, shark-like predator.”

In a ScienceDaily interview entitled “Old fish makes a new splash: Coelacanth find rewrites history of the ancient fish,” Wendruff explains the new escalating dilemma –

“Our coelacanth had a forked tail, indicating it was a fast-moving, aggressive predator, which is very different from the shape and movement of all other coelacanths in the fossil record.”

While the Latimeria chalumnae was a clunky, slow swimmer living 70 million years ago, the newly discovered rebel coelacanth was “dramatically different” – a fast-moving, aggressive predator living much earlier, 240 million years ago.

Given the uniqueness of the new species, Wendruff and Wilson gave the species a new family name − Rebellatricidae, with a full species name of Rebellatrix divaricerca, the only species in the entire family. As Wendruff explains –

“Rebellatrix is dramatically different from any coelacanth previously known.”

Since the new coelacanth “is unique among coelacanths,” Wendruff and Wilson touch on the latest dilemma for evolution –

“Raise[s] questions about long-held ideas concerning the evolution of coelacanth body forms and the mode of locomotion.”

Interestingly, in the book Why Evolution is True, evolution biologist Jerry Coyne of the University of Chicago never refers to the coelacanth as evidence supporting the theory of evolution for good reasons. In 2011,  Coyne won the “Emperor Has No Clothes “award from the Freedom from Religion Foundation.

Coyne won the “Emperor Has No Clothes “award from the Freedom from Religion Foundation.

The new R. divaricerca coelacanth, rather than filling, adds more gaps to the fossil record. Empty gaps, however, are not new to the evolution industry. Molecular biologist Henner Brinkman, of the Université de Montréal, noted in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, conceded in the article entitled “Nuclear protein-coding genes support lungfish and not the coelacanth as the closest living relatives of land vertebrates” –

“The colonization of land by tetrapod ancestors is one of the major questions in the evolution of vertebrates.”

Paleontologist Barbara Stahl, in the article Vertebrate History: Problems in Evolution, noted –

“The modern coelacanth shows no evidence of having internal organs preadapted for use in a terrestrial environment.”

In the words of vertebrate paleontologist Robert L. Carroll, of McGill University, in his book entitled “Vertebrate Palaeontology and Evolution” –

“We have no intermediate fossils between Rhipidistian fish [coelacanth] and early amphibians.” Unfortunately, not a single specimen of an appropriate reptilian ancestor is known prior to the appearance of true reptiles. The absence of such ancestral forms leaves many problems of the amphibian—reptile transition unanswered.”

Genesis

The coelacanth, the once-popular biology textbook example of evolution throughout the early twentieth century as scientific evidence supporting Darwin’s theory of evolution, has been undermined by new fossil record discoveries and findings through the genomic revolution.

The coelacanth, the once-popular biology textbook example of evolution throughout the early twentieth century as scientific evidence supporting Darwin’s theory of evolution, has been undermined by new fossil record discoveries and findings through the genomic revolution.

With the discovery of new evidence, the once-popular coelacanth saga is slowly vanishing from the evolution industry landscape. The evidence from the coelacanth, however, is compatible with the Genesis account written by Moses

In the words of Carolus Linnaeus (pictured left), a Swedish botanist, physician, and zoologist, credited for developing our modern system of naming organisms called binomial nomenclature, wrote during the Scientific Revolution –

“The Earth’s creation is the glory of God, as seen from the works of Nature by Man alone.”

Refer to the Glossary for the definition of terms and to Understanding Evolution to gain insights into understanding evolution.

2020 Update

- The phylogenetic analysis of the coelacanth genome precludes the fish from being a transitional link from fish to land-walking amphibians. The study team, led by Chris T. Amemiya, published their paper entitled “The African coelacanth genome provides insights into tetrapod evolution” in the journal of Nature (April 2013), concluding –

“Through a phylogenomic analysis, we conclude that the lungfish, and not the coelacanth, is the closest living relative of tetrapods.”

- Didier Casane and Patrick Laurenti in the article entitled “Why coelacanths are not ‘living fossils, ’a review of molecular and morphological data,” published in BioEssays, Insight & Perspectives, (February 2013), argue –

“Finally, we emphasize that concepts such as ‘living fossil,’ ‘basal lineage,’ or ‘primitive extant species’ do not make sense from a tree‐thinking perspective.”

“Latimeria was first labeled as a ‘living fossil’ because the fossil genera were known before the extant species was discovered, erroneous biological interpretations have grown, and reports still show little morphological and molecular evolution…. We hope that this review will contribute to dispelling the myth of the coelacanth as a ‘living fossil’ and help biologists keep in mind that actual fossils are dead.”

- Michał Zatoń et al., of the University of Silesia, in the report entitled “The first direct evidence of a Late Devonian coelacanth fish feeding on conodont animals,” in the journal Science Nature (2017), identified a fossilized coelacanth in Poland –

“We describe the first known occurrence of a Devonian coelacanth specimen from the lower Famennian of the Holy Cross Mountains, Poland, with a conodont element preserved in its digestive tract.”

WIKIPEDIA

“Its discovery 66 million years after its supposed extinction makes the coelacanth the best-known example of a Lazarus taxon, an evolutionary line that seems to have disappeared from the fossil record only to reappear much later. Since 1938, West Indian Ocean coelacanth has been found in Comoros, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, Madagascar, in iSimangaliso Wetland Park, and off the South Coast of Kwazulu-Natal in South Africa.”

“More closely related to tetrapods than to the ray-finned fish, coelacanths were [once] considered transitional species between fish and tetrapods.”

“The vertebrate land transition is one of the most important steps in our evolutionary history. We conclude that the closest living fish to the tetrapod ancestor is the lungfish, not the coelacanth. However, the coelacanth is critical to our understanding of this transition, as the lungfish have intractable genome sizes (estimated at 50–100Gb).”

“One reason the coelacanths are evolving so slowly is the lack of evolutionary pressure on these organisms.”

“In July 1998, the first live specimen of Latimeria menadoensis was caught in Indonesia. Approximately 80 species of coelacanth have been described, including the two extant species. Before the discovery of a live specimen, the coelacanth time range was thought to have spanned from the Middle Devonian to the Upper Cretaceous period. Although fossils found during that time were claimed to demonstrate a similar morphology, recent studies have expressed the view that coelacanth morphologic conservatism is a belief not based on data.”

“Coelacanths are ovoviviparous, meaning that the female retains the fertilized eggs within her body while the embryos develop during a gestation period of over a year.”

Rebellatrix divaricerca – evolution not discussed.

Evolution 101 –

“In fact, some lineages have changed so little for such a long time that they are often called living fossils. Coelacanths comprise a fish lineage that branched off of the tree near the base of the vertebrate clade. Until 1938, scientists thought that coelacanths went extinct 80 million years ago. But in 1938, scientists discovered a living coelacanth from a population in the Indian Ocean that looked very similar to its fossil ancestors. Hence, the coelacanth lineage exhibits about 80 million years’ worth of morphological stasis.” I.e., not evolution.

Smithsonian Institute

“The coelacanth’s evolutionary relationships are a matter of controversy. There are several competing hypotheses and many unresolved questions, in large part owing to the many unusual characters found in coelacanths. Experts largely agree that coelacanths are primitive osteichthyans or bony fishes (as opposed to cartilaginous fish, such as sharks and rays) and that their closest living relatives are the primitive lungfishes (known from freshwaters of South Africa, Australia, and South America), but they disagree on the exact placement of the coelacanth in the evolutionary history of vertebrates. Coelacanths might best be described as occupying a side branch in the basal portion of the vertebrate lineage, closely related to but distinct from the ancestor of tetrapods (four-legged vertebrates).”