Inheritance is the second of the five principles of natural selection introduced by Charles Darwin in The Origin of Species. While Darwin knew that inheritance plays a crucial role in natural selection, he was conflicted over how it works, noting –

“The laws governing inheritance are for the most part unknown.”

Niles Eldredge, of the American Museum of Natural History, introduced the V.I.S.T.A. framework to codify the principles of Darwin’s theory. The five structural principles of natural selection are variation, inheritance, selection, time, and adaptation.

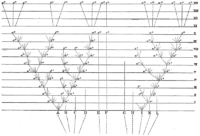

In 1837, nearly twenty years before publishing The Origin of Species, Darwin drew his first sketch linking inheritance to speciation (pictured left).

Inheritance Structure

Darwin’s structure of inheritance is essential for understanding his theory, since inheritance plays a “chief part” in natural selection. As Darwin explains in The Origin of Species –

“The most important consideration is that the chief part of the organisation of every being is simply due to inheritance.”

Inheritance is the biological process by which information is passed from one generation to the next. In the only diagram in The Origin of Species (pictured right), Darwin depicts how the principles of inheritance might lead to the formation of new species over time.

Inheritance is the biological process by which information is passed from one generation to the next. In the only diagram in The Origin of Species (pictured right), Darwin depicts how the principles of inheritance might lead to the formation of new species over time.

Of the original eleven species (A–L), the species designated “I” evolved into six distinct species over fourteen generations. As described (page 94) by Darwin –

“The six descendants from (I) will form two sub-genera or genera… the six descendants from (I) will, owing to inheritance alone.”

The six species emerging from species “I” over fourteen generations are depicted at the top of the diagram. These are denoted as n14, p14, w14, y14, u14, and z14. Each horizontal line, Darwin explains, “may represent each a thousand or more generations… up to the fourteen-thousandth generation.”

However, Darwin’s theory never gained widespread acceptance among naturalists, even at the time. The subsequent transitions from nineteenth-century antiquated inheritance concepts to the Genomic Revolution are among the most significant in modern science.

Building the Structure

Darwin built his theory of natural selection by logically integrating popular beliefs about nature. In building his inheritance structure, Darwin describes his approach –

Darwin built his theory of natural selection by logically integrating popular beliefs about nature. In building his inheritance structure, Darwin describes his approach –

“By continuing the same process for a greater number of generations (as shown in the diagram in a condensed and simplified manner), we get eight species, marked by the letters between a14 and m14, all descended from (A). Thus, as I believe, species are multiplied, and genera are formed.”

The diagram is a logical deductive construct from popular beliefs rather than any testable empirical evidence. Darwin frequently reiterates his “I believe” approach, writing –

“I believe that animals are descended from at most only four or five progenitors, and plants from an equal or lesser number.”

This building framework approach was advocated by the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes (pictured above), a leader of the Age of Enlightenment. Two primary principles of the Enlightenment movement were reason and liberty, independent of empirical evidence.

Within this cultural context, Darwin integrated the popular mechanism of blending inheritance with a concept he called pangenesis.

Blending Inheritance

Blending inheritance was the predominant theory of inheritance during the nineteenth century. Darwin (pictured right) refers to blending in The Origin of Species twenty times. However, Darwin was skeptical of “blending inheritance,” noting why –

“If you cross two exceedingly close races or two slightly different individuals of the same race, then, in fact, you annul and obliterate the differences.”

Ultimately, blending inheritance would only result in homogenized populations with intermediate characteristics. As a result, new variants developed in one generation could not be preserved in subsequent generations.

Nine years following the 1859 publication of The Origin of Species, Darwin finally published his theory of inheritance. The two editions of the book, entitled The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication, were first published in 1868 as two volumes.

Pangenesis

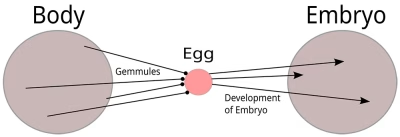

Darwin named his theory of inheritance pangenesis and introduced the concept of gemmules. The word comes from the Greek words pan (a prefix meaning “whole”, “encompassing”) and genesis (“birth”) or genos (“origin”). However, Darwin noted –

Darwin named his theory of inheritance pangenesis and introduced the concept of gemmules. The word comes from the Greek words pan (a prefix meaning “whole”, “encompassing”) and genesis (“birth”) or genos (“origin”). However, Darwin noted –

“The hypothesis of Pangenesis, as applied to the several great classes of facts just discussed, no doubt is extremely complex.”

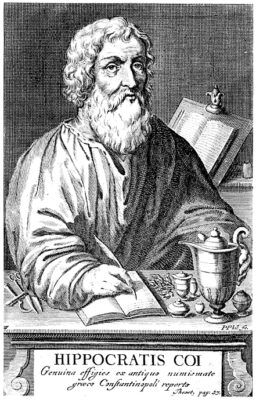

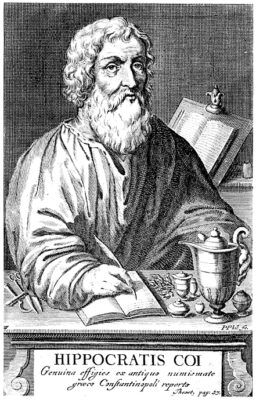

Pangenesis reflected, in part, ideas advanced by the ancient Greek philosopher Hippocrates (pictured left). In Darwin’s view, Hippocrates’ version was “almost identical with mine.” The theory integrated emerging new concepts, specifically cell theory.

Cell theory accounts for the basic structural units of all living things and the basic reproductive units. Gemmules function to regulate initial development, new development, and regeneration. Pangenesis accounts for the inheritance of acquired traits.

Gemmules

Within the concept of pangenesis, Darwin envisioned every cell in the body containing gemmules (pictured right). These are released into circulation and aggregate in reproductive organs to contribute to the formation of offspring. Seven years later, in 1875, Darwin published the second edition of this two-volume set.

Within the concept of pangenesis, Darwin envisioned every cell in the body containing gemmules (pictured right). These are released into circulation and aggregate in reproductive organs to contribute to the formation of offspring. Seven years later, in 1875, Darwin published the second edition of this two-volume set.

In modern terms, gemmules could explain inheritance, development, regeneration, and the persistence of variation despite blending. Gemmules were envisioned as physical conveyors of inheritance, including acquired characteristics.

Pangenesis appears 39 times and gemmules 151 times in The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication. Surprisingly, neither pangenesis nor gemmule appears in any of the editions of The Origin of Species.

By introducing the concept of gemmules, Darwin seemed to have a testable scientific mechanism of inheritance.

Testing Pangenesis

Francis Galton (pictured left), a British scientist knighted by the King and Darwin’s half-cousin, coordinated with Darwin to perform a series of blood transfusions in different colored rabbits to test Darwin’s pangenesis theory scientifically.

Francis Galton (pictured left), a British scientist knighted by the King and Darwin’s half-cousin, coordinated with Darwin to perform a series of blood transfusions in different colored rabbits to test Darwin’s pangenesis theory scientifically.

If pangenesis were true, the infusion of blood from a white-colored rabbit, when infused into a black-colored rabbit, would influence the color of the offspring due to the gemmules. In March 1871, Galton read his test results to the Royal Society and later published these in the Proceedings of the Royal Society entitled “Experiments in Pangenesis, by Breeding from Rabbits.”

However, contrary to expectations, the black rabbits with white rabbits’ blood produced black offspring. Galton concluded gemmules do not exist, undermining Darwin’s theory of pangenesis. In his detailed sixteen-page report, Galton concluded –

“I have now made experiments of transfusion and cross circulation on a large scale in rabbits, and have arrived at definite results, negativing, in my opinion, beyond all doubt the truth of the doctrine of Pangenesis.”

Plagiarized Concept

The essence of Darwin’s pangenesis theory was well known among the academic elite, with roots in Greek philosophy. Yet Darwin publicly denied any foreknowledge even though his grandfather, Erasmus Darwin (pictured left), argued for pangenesis in Zoonomia –

The essence of Darwin’s pangenesis theory was well known among the academic elite, with roots in Greek philosophy. Yet Darwin publicly denied any foreknowledge even though his grandfather, Erasmus Darwin (pictured left), argued for pangenesis in Zoonomia –

“All animals undergo perpetual transformations, which are in part produced by their own exertions… and many of these acquired forms or propensities [acquired characteristics] are transmitted to their posterity [future generations].”

While Erasmus called inheritable “transformations” a product of “their own exertions,” these are what Darwin called gemmules. As WIKIPEDIA explains –

“In 1801, Erasmus Darwin advocated a hypothesis of pangenesis in the third edition of his book Zoonomia.“

Darwin’s Denial

T he month following the publication of Variation Under Domestication, Darwin responded to a presumed now-lost letter from William Ogle, an English physician fluent in classical Greek. In his reply, wishing he had known about pangenesis earlier, Darwin wrote –

he month following the publication of Variation Under Domestication, Darwin responded to a presumed now-lost letter from William Ogle, an English physician fluent in classical Greek. In his reply, wishing he had known about pangenesis earlier, Darwin wrote –

“I thank you most sincerely for your letter which is very interesting to me. I wish I had known of these views of Hippocrates (pictured left), before I had published, for they seem almost identical with mine—merely a change of terms—& an application of them to classes of facts necessarily unknown to this old philosopher. The whole case is a good illustration of how rarely anything is new… pangenesis has been a wonderful relief to my mind, (as it has to some few others) for during long years I could not conceive any possible explanation of inheritance.”

However, Conway Zirkle, historian of science at the University of Pennsylvania, considers Darwin’s “wish” a fabrication. In his article “The Inheritance of Acquired Characteristics and the Provisional Hypothesis of Pangenesis” in the American Naturalist, published in 1935, Zirkle explains –

“The hypothesis of pangenesis is as old as the belief in the inheritance of acquired characters. It was endorsed by Hippocrates (pictured left), Democritus, Galen, Clement of Alexandria, Lactantius, St. Isidore of Seville, Bartholomeus Anglicus, St. Albert the Great, St. Thomas of Aquinas, Peter of Crescentius, Paracelsus, Jerome Cardan, Levinus Lemnius, Venette, John Ray, Buffon, Bonnet, Maupertuis, von Haller, and Herbert Spencer.”

Without an operational theory of inheritance, the influence of Darwin’s theory increasingly waned during the late nineteenth century. However, the rediscovery of Mendel’s theory of inheritance by German geneticist Carl Correns re-ignited interest in Darwin’s theory of natural selection at the turn of the century.

Darwin’s Critics

However, pangenesis generated even more questions than answers. Critics also noticed that Darwin’s theory was essentially a reversion of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s blending inheritance theory of acquired characteristics, including Charles Lyell (pictured right), his closest colleague. In an attempt to distance himself from Lamarck, Darwin wrote a rather curt letter to Lyell –

However, pangenesis generated even more questions than answers. Critics also noticed that Darwin’s theory was essentially a reversion of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s blending inheritance theory of acquired characteristics, including Charles Lyell (pictured right), his closest colleague. In an attempt to distance himself from Lamarck, Darwin wrote a rather curt letter to Lyell –

“You refer repeatedly to my view as a modification of Lamarck’s doctrine of development & progression; if this is your deliberate opinion, there is nothing to be said—; but… I can see nothing else in common between the Origin & Lamarck.”

After seven years of work, even Darwin’s skepticism continued, given the criticisms and the seemingly “insurmountable” issues. In the concluding chapter of Variation Under Domestication, Darwin hedgingly waved a white flag –

“The hypothesis of Pangenesis, as applied to the several great classes of facts just discussed, no doubt is extremely complex; but so assuredly are the facts… The difficulty, therefore, which at first appears insurmountable, of believing in the existence of gemmules so numerous and small as they must be according to our hypothesis, has no great weight.”

By introducing the concept of gemmules, Darwin claimed his version of pangenesis as his own.

Darwin Acknowledges the Problem

However, the ultimate “difficulty” with pangenesis eventually proved to be a “great weight,” failing to explain how inheritance integrates with natural selection. As Darwin lamented in his Autobiography –

“My ‘Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication [Variation Under Domestication]’ was begun, as already stated, in the beginning of 1860, but was not published until the beginning of 1868. It was a big book, and cost me four years and two months’ hard labour… In the second volume the causes and laws of variation, inheritance, &c., are discussed as far as our present state of knowledge permits. Towards the end of the work I give my well-abused hypothesis of Pangenesis.”

Last Two Editions Revised

Responding to Galton’s conclusions, Darwin sent a letter in April 1871 to the Proceedings, noting that gemmules may have been in other bodily fluids and that he never inferred that blood contains gemmules. However, conceding to Galton’s conclusions, Darwin hedged –

“As it is, I think everyone will admit that his experiments are extremely curious and that he deserves the highest credit for his ingenuity and perseverance. But it does not appear to me that Pangenesis has, as yet, received its death blow; though from presenting so many vulnerable points, its life is always in jeopardy, and this is my excuse for having said a few words in its defense.”

Interestingly, the second edition of Variation Under Domestication preceded Darwin’s final two editions of the Origin of Species, published in 1869 and 1872. However, pangenesis, “pan-” meaning whole and “genesis” indicating origin, and gemmules never appeared even in these final editions of The Origin of Species.

Weismann’s Test

In 1892, August Weismann (pictured left), a German evolutionary biologist, challenged the viability of Darwin’s pangenesis theory. After removing the tails of 68 white mice over five generations, none of the mice developed any acquired inheritance characteristics, as Darwin predicted. The effect became known as the Weismann Barrier.

In 1892, August Weismann (pictured left), a German evolutionary biologist, challenged the viability of Darwin’s pangenesis theory. After removing the tails of 68 white mice over five generations, none of the mice developed any acquired inheritance characteristics, as Darwin predicted. The effect became known as the Weismann Barrier.

The short answer to the question of whether scientific evidence has validated Darwin’s pangenesis theory is “none.” The Evolution 101 website, sponsored by the University of California, Berkeley, concurs –

“Darwin himself proposed that each cell in an animal’s body released tiny particles [gemmules] that streamed to the sexual organs, where they combined into eggs or sperm. They would then fuse upon mating. But “pangenesis,” as Darwin called it, didn’t hold up to scrutiny.”

However, the concept of pangenesis did not originate with Darwin.

Neo Darwinism

Gregor Mendel, a contemporary of Darwin, falsified the theory of blending inheritance. By studying inheritance patterns in pea plants, Gregor demonstrated that genetic traits are discrete and independent, not blended. Blending inheritance is now regarded as an “obsolete theory in biology.”

However, Darwin never acknowledged Mendel’s findings. Not until the turn of the century were Darwin’s inheritance concepts replaced by Mendel’s theory in academia. The change eventually prompted the renaming of Darwin’s theory as Neo-Darwinism.

Genesis

Darwin’s legacy of inheritance belongs in the halls of history, but not in science classes. The twentieth-century genomic revolution rescued Darwin’s theory of natural selection, armed with a new theory of inheritance – the modern synthesis theory.

Darwin’s legacy of inheritance belongs in the halls of history, but not in science classes. The twentieth-century genomic revolution rescued Darwin’s theory of natural selection, armed with a new theory of inheritance – the modern synthesis theory.

Since then, biotechnology has shown that the modern synthesis theory fails to account for observed inheritance that appears unrelated to genetic coding.

While the Genesis account written by Moses is compatible with scientific evidence, nature operates through mysteries that seemingly defy scientific explanation. As founder of the Scientific Revolution, Francis Bacon (pictured right), a pioneer of the scientific method, explains –

“God of heaven and earth had vouchsafed the grace to know the works of Creation… to discern between divine miracles, works of nature, [and] works of art.”

Developing a scientific consensus on the mechanisms of evolution remains speculative.

Inheritance, Second Principle of Natural Selection is a Theory and Consensus article.

More

Natural selection’s five principles, coined as an acronym and causal sequence, are V.I.S.T.A –

Darwin Then and Now is an educational resource on the intersection of evolution and science, highlighting the ongoing challenges to the theory of evolution.

Move On

Explore how to understand twenty-first-century concepts of evolution further using the following links –

- The Understanding Evolution category showcases how varying historical study approaches to evolution have led to varying conclusions. Subcategories include –

- Studying Evolution explains how key evolution terms and concepts have changed since the 1958 publication of The Origin of Species.

- What is Science explains Charles Darwin’s approach to science and how modern science approaches can be applied for different investigative purposes.

- Evolution and Science feature study articles on how scientific evidence influences the current understanding of evolution.

- Theory and Consensus feature articles on the historical timelines of the theory and Natural Selection.

- The Biography of Charles Darwin category showcases relevant aspects of his life.

- The Glossary defines terms used in studying the theory of biological evolution.