Britain’s peppered moth has long served as an evolution icon. This month, a new genetic discovery unravels the moth’s once iconic status. As ScienceDaily reports –

Britain’s peppered moth has long served as an evolution icon. This month, a new genetic discovery unravels the moth’s once iconic status. As ScienceDaily reports –

“Researchers from the University of Liverpool, have identified and dated the genetic mutation that gave rise to the black form of the peppered moth, which spread rapidly during Britain’s industrial revolution. The new findings solve a crucial missing piece of the puzzle in this iconic textbook example of evolution by natural selection.”

Peppered moths are notable for their unique speckled range of colors from light, shades of gray, to nearly black. The dark moths are also known as melanics or carbonaria. ScienceDaily’s crucial missing piece of evidence, the “jumping gene,” was published this month in the prestigious journal Nature. “From time to time,” however, according to Jerry Coyne, a University of Chicago evolution scientist,

“evolutionists re-examine a classical experimental study and find, to their horror, that it is flawed.”

Imaginary Illustrations

Enshrined as prima facia scientific evidence of Charles Darwin‘s theory of natural selection, the peppered moth emerged as an icon in biology textbooks during the mid-twentieth century. The story starts in 1898, following a severe snowstorm in Providence, Rhode Island. Biologist Hermon Bumpus (pictured right), found a large number of  English sparrows close to death. Bumpus captured and transferred 136 of the sparrows back to his laboratory, where nearly half of them died.

English sparrows close to death. Bumpus captured and transferred 136 of the sparrows back to his laboratory, where nearly half of them died.

In measuring the living and the dead, the survivors tended to be shorter and lighter-weight males. Bumpus concluded that the storm had taken a more significant toll on sparrows that deviated the most from the “ideal type.” This pattern of differential survival, Bumpus claimed, was due to the actions of natural selection. For his work, Bumpus was eventually appointed director of the American Museum of Natural History in 1906.

The Emerging Icon

What would become the epic twentieth-century evolution icon, however, did not take center stage until British geneticist Bernard Kettlewell ventured into the British heartland inhabited by peppered moths, Biston betularia―more than 50 years later. The epicenter of British textile manufacturing powered by coal during the eighteenth-century Industrial Revolution was centered mainly in Manchester and Birmingham, located in the central region.

What would become the epic twentieth-century evolution icon, however, did not take center stage until British geneticist Bernard Kettlewell ventured into the British heartland inhabited by peppered moths, Biston betularia―more than 50 years later. The epicenter of British textile manufacturing powered by coal during the eighteenth-century Industrial Revolution was centered mainly in Manchester and Birmingham, located in the central region.

By the nineteenth century, the emergence of these great industrial cities had covered the area in a blanket of coal dust. The buildings and vegetation became increasingly dark. Areas once inhabited by light-colored moths on lighter-colored vegetation, were now primarily populated by dark-colored moths on darkened vegetation. The transformation is known as industrial melanism.

With a government grant to study industrial pollution in general and the peppered moth in particular, Kettlewell began to collect data from central England in three significant surveys between 1952 and 1972. During this period, however, no measurable changes were observed.

Not dissuaded by the lack of note-worthy findings, Kettlewell designed a field experiment to test Darwin’s theory of natural selection. After breeding populations of light- and dark-peppered moths in his laboratory, the wings were tagged with a paint-dot for tracking.

Kettlewell released the marked moths for the experiment from both groups into two types of wooded areas in central England: coal polluted and coal unpolluted areas. On the night following the release of the moths, traps were set.

In the polluted areas of the 447 dark-colored moths that were marked and released, 28% were trapped, while only 13% of the 137 light-colored moths that were marked and released were trapped. Kettlewell concluded that predatory birds selected the more visible light-colored moths on the pollution-darkened tree trunks, leaving more dark-colored variety to survive and reproduce.

The same experiment was repeated in the unpolluted wooded areas surrounding the county of Dorset, located in southwest England, distanced from the central industrial areas. On the following night, 13% of the light moths and only 6% of the dark moths were trapped. In the words of Kettlewell, the evidence from the peppered moth is –

“… the most striking evolutionary change ever actually witnessed in any organism.”

Adding credence to Kettlewell’s experiment, biologist Nikolaas Tinbergen, who was later awarded a Nobel Prize, video recorded the peppered moths during the day. Sewall Wright called the study –

“… the clearest case in which a conspicuous evolutionary process has actually been observed.”

Kettlewell declared that the “birds act as selective agents, as postulated by [Darwin’s] evolutionary theory” and published an article in Scientific American in 1959 entitled “Darwin’s Missing Evidence.” British geneticist P. M. Sheppard called the phenomenon

“… the most spectacular evolutionary change ever witnessed and recorded by man.”

These tagged British peppered moths quickly emerged as a textbook evolution icon. Biologists, in the 1980s, however, began uncovering the fundamental problems with Kettlewell’s experiment.

Peppered Moth Tested

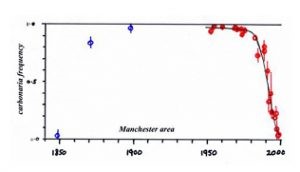

In the wake of antipollution legislation in the 1950s, the darkening effects of industrialization began to reverse gradually. New field studies demonstrated that the proportion of light-peppered moths to be increasing (see graph), dissipating the effects of more than 200 years of coal burning while the proportion of dark melanic moths decreased to the numbers previously recorded by Moses Harris in 1776.

To save the evolution icon, during the 1970s, experiments attempted to replay Kettlewell’s experiment to test. Liverpool biologist Jim Bishop, however, failed to reproduce Kettlewell’s premise that light-peppered moths predominate in unpolluted areas.

D.R. Lees and E. R. Creed later demonstrated that in the little-polluted areas of East England, where the light-colored moths were considered better camouflaged than the dark-colored moths according to Kettlewell’s theory, the dark-colored moths were found to account for 80% of the moths of the total peppered moth population. The investigators concluded:

“Either the predation experiments and tests of conspicuousness to humans are misleading, or some factor or factors in addition to selective predation are responsible for maintaining the high melanic frequencies.”

At best, Kettlewell’s peppered moths serve as an example of adaptation–not biological evolution. Contrary to Kettlewell’s hopeful conviction of observing an evolution icon, no new species has ever or since emerged.

Consensus

In 1999, The Daily Telegraph ran Robert Matthews story “Scientists Pick Holes in Darwin Moth Theory” noting

“scientists admit they do not know the real explanation for the fate of Biston betularia.”

The Washington Times (1999) published Larry Witham’s article –

“Darwinism icons disputed: Biologists discount moth study.”

The New York Times. (2002) published Nicholas Wade’s paper

“Staple of Evolutionary Teaching May Not Be Textbook Case.”

University of Chicago evolutionary biologist, Jerry A. Coyne, (pictured left) published an important observation that Kettlewell overlooked in the journal Nature (1998): peppered moths do not rest on tree trunks which –

“alone invalidates Kettlewell’s release-and-recapture experiments, as moths were released by placing them directly onto tree trunks.”

The “prize horse in our stable of examples” of evolution, Coyne explained, “is in bad shape.” In the words of Japanese biologist Atuhiro Sibatani,

“… the story of industrial melanism should be shelved.”

American biologist Theodore Sargent along with his New Zealander colleagues, Craig Miller and David Lambert, explain

“We contend… that there is little persuasive evidence, in the form of rigorous and replicated observations and experiments, to support this explanation [natural selection].”

Peppered Moth Addiction

The vast majority of biology textbooks covering evolution, however, still use the peppered moth as the classic example of natural selection in action. Bemoaning the continued use of what he termed “misinformation,”  even Stephen Gould, (pictured right) opined –

even Stephen Gould, (pictured right) opined –

“Once ensconced in textbooks, misinformation becomes cocooned and effectively permanent, because … textbooks copy from previous texts.”

Darwin’s dilemma intensifies.

Genesis

The rise and fall “black and white story” ends without any evidence for the emergence of a new species. Therefore, the scientific evidence is compatible with the Genesis account written by Moses. In the words of the father of modern physics, Galilei Galileo, during the Scientific Revolution –

“God is known by nature in his works, and by doctrine in his revealed word.”

Refer to the Glossary for the definition of terms and to Understanding Evolution to gain insights into understanding evolution.