Three years into the pandemic, the origin of COVID-19 is still controversial. Two leading theories are under investigation: natural selection process or genetically engineered – each with vastly different implications. The phylogenetics of coronaviruses is the key to the COVID-19 origin dilemma and gaining insights into the theory of evolution.

Three years into the pandemic, the origin of COVID-19 is still controversial. Two leading theories are under investigation: natural selection process or genetically engineered – each with vastly different implications. The phylogenetics of coronaviruses is the key to the COVID-19 origin dilemma and gaining insights into the theory of evolution.

Coronaviruses are RNA, not DNA viruses. RNA viruses are associated with causing the common cold, influenza, mumps, and measles; coronaviruses in humans can cause respiratory tract infections ranging from no symptoms, mild symptoms to a cytokine storm resulting in organ failure and death in humans.

The steady stream of coronavirus variants, starting with Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and now Omicron, continue driving headline news. This article investigates the massive phylogenetics of coronaviruses generated during the pandemic to explore whether or not coronaviruses, including COVID-19, stem from a natural evolution process to understand the pandemic’s future trajectory.

COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the betacoronavirus, is among the deadliest infectious diseases to have emerged in modern history. The clinical nickname of COVID-19 is the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2, or SARS‑CoV‑2.

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the betacoronavirus, is among the deadliest infectious diseases to have emerged in modern history. The clinical nickname of COVID-19 is the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2, or SARS‑CoV‑2.

Over the past two years, with more than 250 million confirmed cases and over 5 million confirmed deaths, scientists continue to be increasingly astonished by the magnitude, severity, and persistence of the pandemic.

Epidemiologists are puzzled by the phylogenetics of coronaviruses. However, the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) laboratory has studied coronaviruses in bats for over a decade.

Was the virus bioengineered in China’s Wuhan laboratory as a bioterrorist agent? Or is the virus’s origin the result of an ongoing natural adaptive or evolutionary process? As Peter White, Australian virologist notes –

“It feels like we’re watching natural selection taking place in the span of days rather than millennia.”

Over the past two decades, improvements in high-throughput molecular sequencing technologies have transformed molecular biology. Technical advances in automation, robotics, computation, phenomics, and genomics have revolutionized virology.

Scientists’ opportunity to search for the origin of COVID-19 is unparalleled – unveiling the secrets of the molecular interplay between viruses. More significantly, scientists using viruses now have the tools to test the laws of Nature for the scientific validity of evolution – molecule by molecule. Fascination with this intersection of nature and technology is revolutionary.

Discovery of Viruses

The term “virus” was coined during the fourteenth century from the Latin neuter term vīrus meaning poison. However, isolating the virus would take yet another 500 years. In 1892, Russian botanist Dmitri Ivanovsky was the first to filter out a seemingly viral-like agent causing rampant disease in the Crimea tobacco plants.

The term “virus” was coined during the fourteenth century from the Latin neuter term vīrus meaning poison. However, isolating the virus would take yet another 500 years. In 1892, Russian botanist Dmitri Ivanovsky was the first to filter out a seemingly viral-like agent causing rampant disease in the Crimea tobacco plants.

To test Ivanovsky’s hypothesis, Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck published the results of his filtration experiments in 1898, validating Ivanovsky’s hypothesis. Ivanovsky and Beijerinck are known as the co-founders of virology.

Viruses are tiny, only a fraction of the size of a typical genome. Compared to bacteria, viruses are 1,000 times smaller. Aside from size, visualization is elusive since viral species, unlike all other known life forms, although uniquely distinctive, are not cellular.

In the early 1930s, emerging electron microscope advances would prove to be a game-changer. By 1939, German physicist Ernst Ruska and colleagues were the first to visualize the tobacco virus (pictured right) using an electron microscope with higher resolving power – up to 100,000 times more. Since then, viruses have been found inhabiting every known ecosystem on Earth.

“Coronavirus” is derived from the Latin word corona, meaning crown or wreath, borrowing from the Greek κορώνη korṓnē. In the 1960s, Scottish physicists June Almeida and David Tyrrell, using an electron microscope, observed an image of a coronavirus for the first time.

First Coronavirus Infection

The earliest indication of coronavirus infections in animals emerged in the late 1920s—the first reported coronavirus-induced upper-respiratory tract disease case was in 1933 on a North Dakota chicken farm.

Not until 1936 was the causative agent updated and officially renamed Avian coronavirus. A revolution in the emerging field of virology followed these early findings. Nearly a century later, according to a 2021 ScienceDaily article “Scientists identify more than 140,000 virus species in the human gut” –

Not until 1936 was the causative agent updated and officially renamed Avian coronavirus. A revolution in the emerging field of virology followed these early findings. Nearly a century later, according to a 2021 ScienceDaily article “Scientists identify more than 140,000 virus species in the human gut” –

“Viruses are the most numerous biological entities on the planet.”

Since the first electron microscopic image of a coronavirus captured by Almeida and Tyrrell in 1964, viruses have been found in all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Infectious diseases specialist, Stephen Morse (pictured left), estimates the number of undiscovered virus species in mammals alone exceeds 320,000.

Origin of Viruses

The Earth’s most diverse and abundant biological entity is viruses, yet controversy surrounds their origin. Viruses are unlike any other form of life; scientists even differ on whether viruses should be considered a form of life or just organic structures interacting with living organisms.

While some suggest viruses evolved from plasmids or unknown bacteria, viruses appear to be unique life forms without any known evolutionary forerunners. Viruses are the smallest of all known forms of life candidates in genome size.

The fossil record sheds little light on the origin of viruses. Even though molecular components of viruses can undergo mineralization, the fossil viral record has yet to reveal any secrets to its origins. However, three main hypotheses are currently the most popular: the regressive hypothesis, the cellular origin hypothesis, and the co-evolution hypothesis. As WIKIPEDIA explains –

“To date, such analyses have not proved which of these hypotheses is correct. It seems unlikely that all currently known viruses have a common ancestor.”

Viruses are polyphyletic – meaning they have multiple origins without any unifying common genes or common ancestor. Viruses have the classic chicken or the egg first evolution dilemma; did viruses precede or follow the host?

Virus Naming Convention

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) was established in 1966 at the International Congress for Microbiology in Moscow, Russia, to standardize the naming of viruses. The first list of viral species was published in 1971.

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) was established in 1966 at the International Congress for Microbiology in Moscow, Russia, to standardize the naming of viruses. The first list of viral species was published in 1971.

Since then, the number of species identified has continued to increase. In 2017, less than 5,000 species were listed; the October 2021 list includes over 9,000 species. However, even the committee’s list vastly underestimates the actual number since at least 140,000 species have been isolated from the human gut alone.

However, no transitional or intermediate species have yet been identified in the known viral species, scientifically undermining Charles Darwin‘s theory. Darwin mentioned the same problem more than a century ago. In the Origin of Species, noted –

“The distinctiveness of specific forms and their not being blended together in innumerable transitional links is a very obvious difficulty.”

An alternative classification system for viruses remains an ongoing unresolved taxonomy challenge in virology. Viruses are “organisms at the edge of life.”

Paleovirology

Paleovirology is a field of study focusing on the origin and history of viruses, primarily studying molecular evidence since viruses have no fossilizable cellular structures. Viruses are an invaluable model for testing evolution, given the vast number of viral species with the highest mutation rate of any life form.

Paleovirology is a field of study focusing on the origin and history of viruses, primarily studying molecular evidence since viruses have no fossilizable cellular structures. Viruses are an invaluable model for testing evolution, given the vast number of viral species with the highest mutation rate of any life form.

The calculated date for the origin of coronaviruses is estimated between 3300 to 2400 BCE. However, when using a nucleotide molecular clock dating model, the origin of coronaviruses is estimated at 10,000 years ago. A common ancestor, however, has yet to be identified.

Bloomberg journalist, David Fickling (pictured left), asked Peter White (pictured right), Professor in Microbiology and Molecular Biology at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia, “What makes viral evolution, and broadly evolution of pandemic diseases, different from evolution elsewhere in Nature? It feels like we’re watching natural selection taking place in the span of days rather than millennia.” White answered –

evolution, and broadly evolution of pandemic diseases, different from evolution elsewhere in Nature? It feels like we’re watching natural selection taking place in the span of days rather than millennia.” White answered –

“The answer to that lies in the speed of evolution… It will take generations, hundreds of years to change phenotypes for most mammals, but with viruses, it’s very quick.”

However, is this viral “evolution” a speciation event or an adaptive process? The difference may seem subtle, but the implications are immense. Phylogenetics demonstrates the difference.

Biology of Viruses

As Earth’s smallest life form, viruses are invisible even with an optical microscope; they are one-hundredth the size of most bacteria. More than a thousand viruses fit inside a single bacterial cell.

As Earth’s smallest life form, viruses are invisible even with an optical microscope; they are one-hundredth the size of most bacteria. More than a thousand viruses fit inside a single bacterial cell.

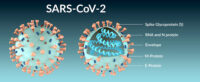

Coronaviruses (pictured left) are one of the largest RNA viruses, with a genome size of approximately 30,000 nucleotides. A membrane protein surrounds the RNA with spike and envelope proteins.

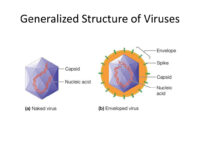

Viruses are known as virions and metabolically inert when outside of a living host cell. Viruses must invade and highjack host molecular machinery to reproduce. Each virion contains an inner genome core of RNA (ribonucleic acid) or DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) surrounded by a glycoprotein envelope – but never both.

Coronaviruses’ inner genome core consists of a single strand of positive-sense RNA. The positive-sense genome functions as a messenger RNA (mRNA) directly translatable into viral proteins by the host cell’s ribosomes.

Compared to DNA viruses, RNA viruses are more prone to copying errors. Nearly 3 percent of each coronavirus copy contains a new random mutation during replication. Each mutated virus is called a variant.

Variants

Mutations drive genetic variations affecting the degree of viral transmissibility and virulence. Not all mutation-induced amino acid changes in the spike protein, however, lead to a change in viral characteristics.

Mutations drive genetic variations affecting the degree of viral transmissibility and virulence. Not all mutation-induced amino acid changes in the spike protein, however, lead to a change in viral characteristics.

The rate of coronavirus mutations is relatively low compared to other infective viruses. As Senior science writer the journal Nature, Ewen Callaway (pictured right), in the article “Beyond Omicron: what’s next for COVID’s viral evolution,” notes –

“Genome sequencing early in the pandemic showed the virus diversifying and picking up about two single-letter mutations per month. This rate of change is about half that of influenza and one-quarter that of HIV, thanks to an error-correcting enzyme coronaviruses possess that is rare among other RNA viruses.”

HIV, thanks to an error-correcting enzyme coronaviruses possess that is rare among other RNA viruses.”

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) labels variants with specific genetic markers affecting host receptor binding as “variants of interest” and “variants of concern” stains with specific genetic markers and known to have higher transmissibility and virulence. The CDC defines “variants of concern” (VOC) as –

“When there is evidence of an increase in transmissibility, more severe disease (for example, increased hospitalizations or deaths), a significant reduction in neutralization by antibodies generated during previous infection or vaccination, reduced effectiveness of treatments or vaccines, or diagnostic detection failures.”

Most mutations have little or no effect on the characteristics of a virus. However, some genetic mutations cause meaningful changes.

Scientists worldwide have now cataloged the sequence of more than 6 million genomes during our global fight to track variants and control outbreaks. As of January 2021, approximately 25,000 out of the 29,800 sites in the SARS-CoV-2 genome carry mutational differences.

Virus Transmissibility and Infectivity

Human viral diseases typically originate from a wildlife source. An envelope, the outermost layer of many viruses, including coronaviruses, protects the genome and coordinates the viral invasion of the host immune system. Not all viruses have an envelope.

Human viral diseases typically originate from a wildlife source. An envelope, the outermost layer of many viruses, including coronaviruses, protects the genome and coordinates the viral invasion of the host immune system. Not all viruses have an envelope.

On the surface lining of the envelope are glycoproteins ( pictured left). These proteins identify and bind the virus to receptor sites on the cellular membranes of the host. Mutations in these protein-coding genes can affect the degree of transmissibility and infectivity.

The glycoproteins surrounding the genetic material are called the capsid (pictured right) – the virus’s protein shell. Viral transmission occurs when the viral envelope fuses with a host membrane, allowing the viral genome to enter and infect the host.

The capsid also determines the range of host species. As virologist Guillermo Blanco-Rodriguez in the article “The Viral Capsid: A Master-Key to Access the Host Nucleus,” published in the journal Viruses explains –

“Viruses use the capsid to manipulate the nuclear import machinery. However, the particular tactics employed by each virus to reach the host chromatin compartment are very different.”

The glycoproteins of the capsid are called capsomeres. However, not all RNA viruses have a capsid envelope. These are known as capsid-less RNA viruses. Non-enveloped viruses are more virulent than enveloped viruses and survive on inert surfaces for extended periods.

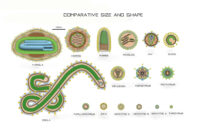

Most viruses have one of five main shapes, with virion sizes ranging from 20 nanometers (nm) to 500 nm in diameter. Coronaviruses, however, have only one shape. The club-shaped glycoprotein envelope with projections, known as spikes, gives the virus its characteristic “coronal” appearance with a smaller diameter of 80 to 200 (nm).

Since capsids play an essential role in the life cycle of the vast majority of viruses, a theory of viral evolution based on capsids gained traction. However, as National Institute of Health (NIH) Senior Investigator, Eugene V. Koonin, argues in the article “The complexity of the virus world” published in the Nature Reviews Microbiology –

“We think that the capsid-centric approach and the associated definition of a virus are unnecessarily rigid and could lead to neglect of important aspects of the evolutionary dynamics of the virus world (virosphere) and even to overt contradictions.”

Coronavirus Divisions

In the biological classification hierarchy, coronaviruses are of the Orthocoronavirinae subfamily divided into four genera: Alphacoronavirus (32), Betacoronavirus (27), Gammacoronavirus (10), and Deltacoronavirus (5), plus one unclassified Orthocoronavirinae species (number in parenthesis indicates the number of species in the genus). The coronavirus subfamily includes seventy-seven distinctive species.

Coronavirus variants are classified using Greek alphabet letters, i.e., Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron variants; Omicron is the fifteenth VOC and the fifteenth letter of the Greek alphabet. The name of each variant follows the sequence of discovery. Notably, no variant is known as an intermediate or transitional link.

Warm-blooded flying vertebrates, bats, and birds are the primary natural reservoir for the coronavirus gene pool. Bats are the primary reservoirs for Alphacoronavirus and Betacoronavirus, while birds are the primary reservoir for Gammacoronavirus– and Deltacoronavirus.

Early Coronavirus Infections

The first reports of coronavirus infections emerged from North American chicken farms in the late 1920s. The chickens developed acute respiratory infections. New-born chicks were especially vulnerable with gasping listlessness resulting in 40–90% mortality rates.

Within a few years, swine, cattle, horses, camels, cats, dogs, rodents, birds, and bats experienced similar coronavirus-like infections. The first reported coronavirus infection in humans was identified in the mid-1960s. Before the pandemic, coronaviruses accounted for 15% of common cold infections in humans.

Most of the human viral and nonviral infectious diseases have existed for centuries. Measles, influenza, cholera, smallpox, falciparum malaria, dengue, and HIV are human pathogenic viruses passed on from animals to humans – called host-switching or zoonosis.

Origin of Human Coronavirus Infectivity

In 2003, a previously unknown betacoronavirus named SARS-CoV-1 emerged suddenly in China and quickly spread to 29 other countries killing 813 of the 8,809 infected people. SARS-CoV’s virus name is an acronym for its associated disease: “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus.” The SARS-CoV-1 pandemic launched scientific interest in coronaviruses.

In 2003, a previously unknown betacoronavirus named SARS-CoV-1 emerged suddenly in China and quickly spread to 29 other countries killing 813 of the 8,809 infected people. SARS-CoV’s virus name is an acronym for its associated disease: “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus.” The SARS-CoV-1 pandemic launched scientific interest in coronaviruses.

Nearly a decade later, another previously unknown β-coronavirus named Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus in 2012 (MERS-CoV) emerged in the Arabian Peninsula to cause high case-fatality human infections.

Although MERS-CoV is closely related to SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV mortality rates are significantly lower. In late 2019, the third wave of severe human coronavirus infections reemerged in China. Since then, global deaths have soared to over 5 million.

SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-1 enter mammalian cells via angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors (pictured left). ACE2 receptors are highly concentrated in the human heart and kidneys, explaining the disease progression in patients with comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease.

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2, SARS‑CoV‑2, or COVID-19, differs from all known coronaviruses.

COVID-19 Origins

Coronaviruses challenge and astonish scientists. How did a relatively benign virus suddenly appear deadly? The two leading hypotheses are 1) engineered in a Chinese Wuhan virology laboratory or 2) newly mutated viral form host-switched, i.e., a zoonotic origin.

Coronaviruses challenge and astonish scientists. How did a relatively benign virus suddenly appear deadly? The two leading hypotheses are 1) engineered in a Chinese Wuhan virology laboratory or 2) newly mutated viral form host-switched, i.e., a zoonotic origin.

While the origin of COVID-19 has widespread implications, the issue is far from settled. As noted in the journal Nature December 2021 review article entitled “The emergence, genomic diversity and global spread of SARS-CoV-2” –

“Whether SARS-CoV-2 was introduced through a laboratory accident or whether it has been genetically manipulated is highly debatable.”

Evidence for host-switching is the leading hypothesis for both SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV pandemics. While bats served as the viral host reservoir for both pandemics and civets as the intermediate viral host for SARS-CoV-1, camels served as the intermediate for MERS-CoV. In both pandemics, the viral reservoirs were close to the infected humans.

Central to Covid’s origin dilemma is how a virus generally found in horseshoe bats in caves in the far south of China turned up in a city a thousand miles north in Wuhan.

Wuhan, China

The early reported COVID-19 cases in Wuhan were associated with the live-animal Huanan Seafood Market – located in the Hubei Province 20 miles from the Wuhan laboratory. This market has long been suspected as the location for the initial zoonotic, cross-species transmission event.

The early reported COVID-19 cases in Wuhan were associated with the live-animal Huanan Seafood Market – located in the Hubei Province 20 miles from the Wuhan laboratory. This market has long been suspected as the location for the initial zoonotic, cross-species transmission event.

However, the origin of the COVID-19 pandemic is significantly different from SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV epidemics. While many animals sampled from the local area tested positive for the virus during the SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV epidemics, none of the samples obtained from a wide range of animals surrounding the market tested positive for COVID-19.

As Wall Street Journal article, “Science Closes In on Covid’s Origins” (October 2021), by Richard Muller (pictured right) and Steven Quay explains –

“Chinese scientists searched for a host in early 2020, testing more than 80,000 animals from 209 species, including wild, domesticated, and market animals. As the WHO investigation reported, not a single  animal infected with SARS-CoV-2 was found. This finding strongly favors the lab-leak theory. We can only wonder if the results would have been different if the animals tested had included the humanized mice kept at the Wuhan Institute of Virology.”

animal infected with SARS-CoV-2 was found. This finding strongly favors the lab-leak theory. We can only wonder if the results would have been different if the animals tested had included the humanized mice kept at the Wuhan Institute of Virology.”

Scientists did locate a close COVID-19 relative; however, it was in the Yunnan Provence – a thousand miles away and differed genetically from SARS-CoV-2. The National Intelligence Council concluded –

“Based on currently available information, the closest known relatives to SARS-CoV-2 in bats have been identified in Yunnan Province, and researchers bringing samples to laboratories provide a plausible link between these habitats and the city.”

With COVID-19 untraceable to any animal in the market area during late 2019, a natural zoonotic origin is ruled-out. As British journalist Matt Ridley, in The Spectator, the “World’s Oldest Magazine” in the article “The Covid lab leak theory just got even stronger” (November 2021) explains –

“There is also little doubt that the bat carrying the progenitor of the virus lived somewhere else.”

Yunnan to Wuhan

Between 2016 and 2019, viruses from bats in eight countries, including Burma, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, were sent to the Wuhan lab coordinated by the nonprofit EcoHealth Alliance organization headquartered in New York headed by Peter Daszak.

Between 2016 and 2019, viruses from bats in eight countries, including Burma, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, were sent to the Wuhan lab coordinated by the nonprofit EcoHealth Alliance organization headquartered in New York headed by Peter Daszak.

EcoHealth focuses on research to prevent pandemics and promote conservation in hotspot regions worldwide. EcoHealth Alliance received nearly $39 million from the Pentagon beginning in 2013. Numerous emails within the organization uncovered by a lawsuit from the White Coat Waste Project released the following statement –

“All samples collected would be tested at the Wuhan Institute of Virology.”

Gilles Demaneuf, a New Zealand-based data scientist who’s been analyzing this COVID-19 issue, says the natural spillover theory has –

“No explanation for why this would result in an outbreak in Wuhan of all places and nowhere else.”

Ridley, using open-source intelligence from Drastic (Decentralized Radical Autonomous Search Team Investigating COVID-19), an organization of 30 members investigating the pandemic, notes –

“Leaked document revealed in September by Drastic, a confederation of open-source analysts like Demaneuf, sent shock- waves through the scientific community. Dr. Peter Daszak, head of the EcoHealth Alliance, spelled out plans to work with his collaborators in Wuhan and elsewhere to artificially insert novel, rare cleavage sites into novel SARS-like coronaviruses collected in the field, so as to better understand the biological function of cleavage sites. His 2018 request for $14.2 million from the Pentagon to do this was turned down amid uneasiness that it was too risky, but the very fact that he was proposing it was alarming.”

The National Intelligence Council’s conclusions parallel Ridley’s explanation –

“IC (Intelligence Community) analysts do not have higher confidence that SARSCoV-2 was not genetically engineered because some genetic engineering techniques can make modifications difficult to identify and we have gaps in our knowledge of naturally occurring coronaviruses.”

Gap Analysis

A natural COVID-19 source remains unknown since only some of the early Wuhan COVID-19 cases were even linked to the market epidemiologically. While the market may have been the location of the “superspreading” event, the laboratory may have been the location of COVID-19 origins.

A natural COVID-19 source remains unknown since only some of the early Wuhan COVID-19 cases were even linked to the market epidemiologically. While the market may have been the location of the “superspreading” event, the laboratory may have been the location of COVID-19 origins.

The BBC featured the article “Covid origin: Why the Wuhan lab-leak theory is being taken seriously” (May 2021) pointed out –

“In recent weeks, the controversial claim that the pandemic might have leaked from a Chinese laboratory – once dismissed by many as a fringe conspiracy theory – has been gaining traction.”

The article includes information from a classified US Intelligence report stating –

“Three researchers at the Wuhan laboratory were treated in hospital in November 2019, just before the virus began infecting humans in the city.”

As Muller, University of California physicist, and Quay (pictured left above), biotechnology entrepreneur and physician, explains –

“Based on the scientific evidence alone, an unbiased jury would be convinced that SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus escaped after being created in a laboratory using accelerated evolution (a k a gain of function) and gene splicing on the backbone of a bat coronavirus.”

Phylogenetics

The concept of phylogenetics is rooted in the origins of evolution theory. Aristotle, an ancient Greek philosopher, is credited for developing the theory in Historia Animalium. Plotinus, a Roman philosopher, illustrated Aristotle’s concept using his “Great Chain of Being” drawing (pictured left) – also known as “Scala Naturae” in Latin.

The concept of phylogenetics is rooted in the origins of evolution theory. Aristotle, an ancient Greek philosopher, is credited for developing the theory in Historia Animalium. Plotinus, a Roman philosopher, illustrated Aristotle’s concept using his “Great Chain of Being” drawing (pictured left) – also known as “Scala Naturae” in Latin.

In the 13th century, Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas reintroduced a synthesis of Aristotelian concepts into the West, creating a bedrock of academic philosophy and science. “Plenitude, continuity, and gradation” formulated the movement’s three philosophical pillars.

In 1859, Charles Darwin presented a new pillar in The Origin of Species – natural selection. New life forms originate through an evolutionary speciation process illustrated with revised tree diagrams, too. As Darwin describes –

“The process of modification and the production of a number of allied forms necessarily being a slow and gradual process — one species first giving rise to two or three varieties, these being slowly converted into species.”

“Phylogenetic tree” is the twenty-first-century name for evolution’s tree of life diagrams. The tree illustrates proposed evolutionary interrelations of life- forms originating from a common ancestor. As Encyclopedia Britannica explains –

“The ancestor is in the tree trunk; organisms that have arisen from it are placed at the ends of tree branches. The distance of one group from the other groups indicates the degree of relationship; i.e., closely related groups are located on branches close to one another.”

The construction of a phylogenetic tree uses physical evidence obtained from organisms. The types of evidence may include anatomical, morphological, physiological, or molecular; aggregate evidence strengthens the scientific validity of any tree.

Life’s universal common ancestor is the tree’s root, with descendants arranged in successive order along the branches and nodes. The ends of each branch depict the last descendant. As the journal Nature explains in “Nature Education” –

“A phylogenetic tree, also known as a phylogeny, is a diagram that depicts the lines of evolutionary descent of different species, organisms, or genes from a common ancestor.”

The phylogenetic tree serves as the falsification test for Darwin’s theory, as explained in the Origin of Species –

“If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed, which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down.”

Phylogenetics of Coronaviruses

As one of life’s simple and earliest forms, scientists have anticipated uncovering evidence for evolution in viruses – serving as a model of evolution. In 2015, the CDC (laboratory pictured left) used viruses for their tutorial on phylogenetics.

As one of life’s simple and earliest forms, scientists have anticipated uncovering evidence for evolution in viruses – serving as a model of evolution. In 2015, the CDC (laboratory pictured left) used viruses for their tutorial on phylogenetics.

Given the treasure trove of high-quality molecular data, investigators have the genetic evidence necessary to construct a scientifically valid phylogenetic tree for the coronaviruses. As epidemiologist Juan Li explains in the article “The emergence, genomic diversity and global spread of SARS-CoV-2” –

“The genomic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 is by far the largest pathogen genomic sequencing project undertaken, with more than 2.8 million complete genomes generated as of August 2021.”

A phylogenetic tree depicting the lines and transitional links of evolutionary descent of coronaviruses from a common ancestor remains a mystery. As immunologist Tingting Li in the Nature journal article “Phylogenetic supertree reveals detailed evolution of SARS-CoV-2” concedes –

“The origin of SARS-Cov-2 and its evolutionary relationship [phylogenetics] is still ambiguous.”

Lines of Evidence

Physical evidence is essential to validate the theory of evolution scientifically. Evolution predicts physical changes advancing slowly and incrementally over time, resulting in speciation events.

Physical evidence is essential to validate the theory of evolution scientifically. Evolution predicts physical changes advancing slowly and incrementally over time, resulting in speciation events.

While the search has identified closely related coronaviruses, RaTG13 and BANAL-52, 96.1% and 96.8% similar to COVID-19, respectively, neither species are considered transitional links or have a common ancestor.

Intermediate forms, sometimes called transitional links, are the core focus of evolution research. In the Origin of Species, Darwin gave the following advice –

“We should always look for forms intermediate between each species and a common but unknown progenitor.”

However, evidence of coronavirus biomolecular intermediate forms does not exist – as discussed in this article. There are no transitional protein compositions or genetic links, nor any transitional organelles. The sizes and the shapes of each virus are distinct and unique, as is the molecular machinery resulting (pictured right). As a result, each virus’s degree of infectivity and transmissibility is unique and distinctive.

and the shapes of each virus are distinct and unique, as is the molecular machinery resulting (pictured right). As a result, each virus’s degree of infectivity and transmissibility is unique and distinctive.

Significantly, identifying a common ancestor for viruses, including coronavirus, remains an unexplainable mystery.

A consensus from any scientific organization does not exist on the phylogenetics of the coronaviruses. Graham Lawton, science writer for the NewScientist, explains –

“… the holy grail was to build a tree of life, but today that project lies in tatters, torn to pieces by an onslaught of negative evidence.”

As Italian geneticist Giuseppe Sermonti (pictured above left) has long asserted –

“One spur to research on mutations was the hope that an accumulation of these [mutations] might lead to a new species. But this never happened.”

Genesis

The phylogenetics of coronavirus serves as a model of conservation, not evolution. The existence of coronaviruses is compatible with the Genesis account written by Moses.

The phylogenetics of coronavirus serves as a model of conservation, not evolution. The existence of coronaviruses is compatible with the Genesis account written by Moses.

In the words of Louis Pasteur, French chemist and microbiologist, discoverer of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization, and developer of vaccines for Rabies, Diphtheria, Anthrax and discrediting Charles Darwin’s theory of spontaneous generation during the scientific revolution–

“Microscopic being must come into the world from parents similar to themselves… There is something in the depths of our souls which tells us that the world must be more than a mere combination of events.”

Evidence from molecular biology to validate the theory of evolution scientifically still remains speculative.

Phylogenetics of Coronaviruses is a Molecular Biology article.

Darwin Then and Now is an educational resource on the intersection of evolution and science, highlighting the ongoing challenges to the theory of evolution.

Move On

Explore how to understand twenty-first-century concepts of evolution further using the following links –

-

- The Understanding Evolution category showcases how varying historical study approaches to evolution have led to varying conclusions. Subcategories include –

- Studying Evolution explains how key evolution terms and concepts have changed since the 1958 publication of The Origin of Species.

- What is Science explains Charles Darwin’s approach to science and how modern science approaches can be applied for different investigative purposes.

- Evolution and Science feature study articles on how scientific evidence influences the current understanding of evolution.

- Theory and Consensus feature articles on the historical timelines of the theory and Natural Selection.

- The Biography of Charles Darwin category showcases relevant aspects of his life.

- The Glossary defines terms used in studying the theory of biological evolution.

- The Understanding Evolution category showcases how varying historical study approaches to evolution have led to varying conclusions. Subcategories include –

Update

February 3, 2022

The article by Jim Geraghty, a senior political correspondent of National Review, entitled “Made in China: On the Lab-Leak Origin of Covid, Plenty of evidence points to it” adds more details to the origin of the COVID-19 mystery saga.