Selection is the third of the five principles of natural selection introduced by Charles Darwin in The Origin of Species. Darwin wrote –

Selection is the third of the five principles of natural selection introduced by Charles Darwin in The Origin of Species. Darwin wrote –

“Over all these causes of Change, I am convinced that the accumulative action of Selection, whether applied methodically and more quickly, or unconsciously and more slowly, but more efficiently, is by far the predominant Power.”

To explain selection, Darwin drew a parallel between a breeder’s selection process and natural selection, using pigeon breeding (pictured above) as one example. At the time, breeding pigeons was a prestigious pastime for the elite.

V.I.S.T.A.

Niles Eldredge, of the American Museum of Natural History, introduced the V.I.S.T.A. framework to codify the principles of Darwin’s theory. The five structural principles of natural selection are variation, inheritance, selection, time, and adaptation.

Niles Eldredge, of the American Museum of Natural History, introduced the V.I.S.T.A. framework to codify the principles of Darwin’s theory. The five structural principles of natural selection are variation, inheritance, selection, time, and adaptation.

Surprisingly, Darwin never defined how selection actually works, even though Darwin viewed it as a central factor in evolution. In the words of Eldredge –

“When [Darwin] formulated the principle of natural selection, he had discovered the central process of evolution.”

Darwin was not the first to view selection as an essential driving principle in evolution. English zoologist and chemist Edward Blyth had introduced the phrase “natural process of selection” twenty years earlier. In the first chapter of The Origin of Species, Darwin credits Blyth, noting –

“Mr. Blyth, whose opinion, from his large and varied stores of knowledge, I should value more than that of almost anyone.”

While not the first to contemplate a causal role for selection in evolution, Darwin is credited with coining the phrase “natural selection.”

Natural Selection

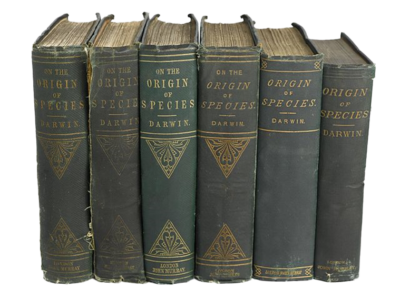

![]() The central importance of selection in Darwin’s concept of evolution is captured in the title of Darwin’s landmark book –

The central importance of selection in Darwin’s concept of evolution is captured in the title of Darwin’s landmark book –

“On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life”

An instant bestseller, all 1,250 printed copies sold on the first day. However, critics quickly challenged his approach to understanding his concept of evolution, for good reasons: Darwin did not define his terms.

Definitions

The hallmarks of scientific work are defined terms that are testable through repeatable empirical observations and measurements. By comparison, the Principia, written by Isaac Newton (1642–1727) more than a hundred years earlier, begins with the definition of his terms.

However, Darwin never defined the terms “selection” or “natural selection.” A style popular during the Enlightenment, Darwin infers definitions of terms and scales of measure. This practice conflicted with the empirical Scientific Method developed earlier by Francis Bacon (1561-1626).

In the first five editions of The Origin of Species, Darwin did not include a Glossary. However, by the last edition, one was added, but WS Dallas compiled it. Darwin added the page footer –

“I am indebted to the kindness of Mr. W. S. Dallas for this Glossary, which has been given because several readers have complained to me that some of the terms used were unintelligible to them. Mr. Dallas has endeavoured to give the explanations of the terms in as popular a form as possible.”

However, Dallas’ Glossary did not include definitions for “selection” or “natural selection.”

Inferences

Understanding selection terms, therefore, has relied on interpreting Darwin’s inferences. In general, though, “natural” is understood as free of intervention, and “selection” is understood as acting with conscious choice.

As a result, Darwin’s explanations were vague, formulated with logical speculations, not scientific terms. But Darwin’s vagueness went beyond speculations, sometimes into the “imaginary.” Darwin explains –

“In order to make it clear how, as I believe, natural selection acts, I must beg permission to give one or two imaginary illustrations.”

This progressive writing style was popular during the Age of Enlightenment. Vagueness gave readers license to speculate independently, a style successfully used by his grandfather, Erasmus Darwin. In Zoonomia, his most widely acclaimed work, Erasmus reasoned –

“Would it be too bold to imagine that in the great length of time, since the earth began to exist… all warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament.”

To address criticisms from friends and foes due to his vague and sometimes conflicting explanations, Darwin revised his bestseller five times. Between the fifth and sixth editions alone, Darwin eliminated 63 sentences, rewrote 1,699 sentences, and added 517 sentences.

To address criticisms from friends and foes due to his vague and sometimes conflicting explanations, Darwin revised his bestseller five times. Between the fifth and sixth editions alone, Darwin eliminated 63 sentences, rewrote 1,699 sentences, and added 517 sentences.

In the first edition, “natural selection” appears 315 times and 405 times in the last. Eventually, in The Origin of Species, Darwin opined –

“Natural selection… is by far the most serious special difficulty which my theory has encountered.”

Even with the revisions, though, Darwin never defined selection or natural selection.

Selective Breeding

In place of defining selection, Darwin developed logical inferences from “imaginary illustrations” and selective breeding. In the first chapter of The Origin of Species, Darwin argued –

“Can the principle of selection, which we have seen is so potent in the hands of man, apply under nature? I think we shall see that it can act most efficiently.”

Darwin envisioned the selective actions of nature as the driver of evolution by choosing between available options, noting –

“The great power of this principle of selection is not hypothetical. It is certain that several of our eminent breeders have, even within a single lifetime, modified to a large extent their breeds of cattle and sheep.”

Inferring that selection is analogous to selective breeding provided a framework for understanding the term. However, it neither defines the term nor offers a framework for understanding the mechanisms of selection.

Mechanisms of Selection

In an article published by Revue Horticole in 1852, French naturalist Charles Victor Naudin (pictured right) predated Darwin’s version of natural selection. However, Darwin critiqued Naudin’s theory in The Origin of Species, beginning with the third edition, noting –

In an article published by Revue Horticole in 1852, French naturalist Charles Victor Naudin (pictured right) predated Darwin’s version of natural selection. However, Darwin critiqued Naudin’s theory in The Origin of Species, beginning with the third edition, noting –

“In 1852, M. Naudin, a distinguished botanist, expressly stated, in an admirable paper on the origin of species… his belief that species are formed analogously as varieties are under cultivation; and the latter process he attributes to man’s power of selection. But he does not show how selection acts under nature.”

What Darwin noted as missing in Naudin’s theory was an explanation of “how” nature performs its selection process. Naudin had no mechanism to explain how nature performs its selection process.

To answer his own question, Darwin introduced the concept of sexual selection.

Sexual Selection

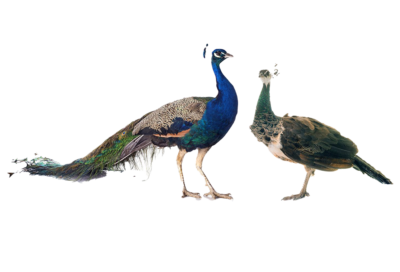

Sexual selection is Darwin’s process to explain how mating traits originated (pictured left). In 1838, contemplating an answer to his own “how selection acts” question, he had written in his “Old and Useless Notes“ –

Sexual selection is Darwin’s process to explain how mating traits originated (pictured left). In 1838, contemplating an answer to his own “how selection acts” question, he had written in his “Old and Useless Notes“ –

“How does Hen determine most beautiful cock, which best singer?”

Sexual selection became Darwin’s answer, demonstrating how nature “selects” through observable processes. While natural selection equips species to struggle for existence, sexual selection is the mechanism that equips them to compete for reproduction. Darwin explains –

“This leads me to say a few words on what I have called Sexual Selection. This form of selection depends, not on a struggle for existence in relation to other organic beings or to external conditions, but on a struggle between the individuals of one sex, generally the males, for the possession of the other sex. The result is not death to the unsuccessful competitor, but few or no offspring.”

The term “sexual selection” appears twenty-one times in The Origin of Species. Describing sexual selection further, Darwin notes –

“Sexual selection has given the most brilliant colours, elegant patterns, and other ornaments to the males, and sometimes to both sexes of many birds, butterflies, and other animals (male/female right).”

The same term appears 104 times in The Descent of Man, published in 1871. However, perhaps not surprisingly, Darwin concedes –

“The precise manner in which sexual selection acts is to a certain extent uncertain.”

Therefore, while sexual selection may explain “why,” it does not explain “how.” A scientific explanation of evolution needed more than what Darwin delivered.

Modern Synthesis Theory of Evolution

In the first half of the twentieth century, the emergence of the Modern Synthesis theory of evolution seemed to shore up Darwin’s shortcomings. The synthesis integrated Darwin’s natural selection, Gregor Mendel’s genetic laws of inheritance, and R.A. Fisher’s (pictured left) population model.

In the first half of the twentieth century, the emergence of the Modern Synthesis theory of evolution seemed to shore up Darwin’s shortcomings. The synthesis integrated Darwin’s natural selection, Gregor Mendel’s genetic laws of inheritance, and R.A. Fisher’s (pictured left) population model.

The modern tools for analyzing DNA, developed in the 1950s, opened a window for studying the molecular mechanisms of inheritance. Since then, a gene-centric approach has primarily driven research on biological evolution.

Modern molecular tools anchored evolutionary theory in the gene as its primary explanatory mechanism. The prospect of a cohesive gene-centric mechanism of evolution prompted Theodosius Dobzhansky (pictured right), geneticist and biologist, to declare in 1973 –

mechanism. The prospect of a cohesive gene-centric mechanism of evolution prompted Theodosius Dobzhansky (pictured right), geneticist and biologist, to declare in 1973 –

“Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.”

Evolutionary theory finally gained the scientific mechanistic depth Darwin lacked. An organism’s genotype, governed by a pair of alleles, contributes to its physical expression, known as phenotype.

Alleles are specific sequences of nucleotides forming the structure of DNA. In diploid organisms, a pair of alleles, one from each parent, determines the characteristics of each species.

Of the five principles of natural selection, selection is the only active driving force. Specifically, selection must act to choose between accepting and eliminating variations.

Attaining a scientific answer to Darwin’s challenge of “how selection acts” seemed increasingly probable with empirical phylogenetic observations in populations.

Selection Types

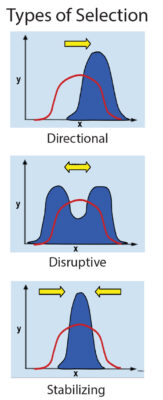

With the race to discover “how selection acts” to change populations across multiple biological levels underway, interpretation was the next step. Twenty-first-century investigators identified three types of selection guiding evolution: directional, disruptive, and stabilizing.

With the race to discover “how selection acts” to change populations across multiple biological levels underway, interpretation was the next step. Twenty-first-century investigators identified three types of selection guiding evolution: directional, disruptive, and stabilizing.

-

- Directional selection favors one extreme phenotype over other extreme and moderate types. Domestic breeding applies directionally.

- Disruptive and diversifying selection favors extreme phenotypes over intermediate types. Divergent drives populations towards speciation.

- Stabilizing selection favors intermediate phenotypes over extreme types, the opposite of disruptive selection. Stabilizing is conservational.

Balancing, fluctuating, and negative, also known as purifying selection, are considered minor types of guiding selection. In practice, however, categorizing the type of selection guidance has been inconsistently reported in the literature.

Inconsistencies have been reported in the historical example of natural selection involving Darwin’s finches and Kettlewell’s peppered moths. Some classify these as directional selection, whereas others classify them as disruptive selection. Homo sapiens have been variably classified as examples of stabilizing and directional selection.

In the quest to explain “how selection acts” scientifically, real-time study models have been developed.

Laboratory Observations

The Genomic Revolution provided scientists with tools to observe the genetic mechanisms underlying natural selection. In 1988, biologist Richard Lenski at the University of California, Irvine, launched the longest-running experiment in the history of evolutionary science.

The Genomic Revolution provided scientists with tools to observe the genetic mechanisms underlying natural selection. In 1988, biologist Richard Lenski at the University of California, Irvine, launched the longest-running experiment in the history of evolutionary science.

Coined as the long-term evolution experiment (LTEE), Lenski’s novel experiment monitors successive selection processes associated with progressive environmental changes. Lenski’s 12 distinct Escherichia coli populations (pictured left), isolated in 12 separate flasks (pictured right), have now been maintained continuously for more than three decades.

Coined as the long-term evolution experiment (LTEE), Lenski’s novel experiment monitors successive selection processes associated with progressive environmental changes. Lenski’s 12 distinct Escherichia coli populations (pictured left), isolated in 12 separate flasks (pictured right), have now been maintained continuously for more than three decades.

Cell sizes, growth rates, colony morphologies, and molecular and genomic changes are documented daily. Samples from each of the 12 populations are preserved daily for future study. Over the first 20,000 generations, the bacterial populations in each flask generated hundreds of millions of random mutations.

The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) has funded Lenski’s project from the outset. In 2017, writing for Science Alert, Fiona MacDonald gives context to the significance of Lenski’s (pictured left) study, noting –

The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) has funded Lenski’s project from the outset. In 2017, writing for Science Alert, Fiona MacDonald gives context to the significance of Lenski’s (pictured left) study, noting –

“Scientists have spent the past 30 years carefully tracking evolution across more than 68,000 generations of E. coli bacteria – the equivalent of more than 1 million years of human evolution.”

In 2024, Alejandro Couce (pictured right) and Lenski reported their analysis at the 50,000-generation point in the journal Science. Entitled “Changing fitness effects of mutations through long-term bacterial evolution,” the journal’s editor noted –

In 2024, Alejandro Couce (pictured right) and Lenski reported their analysis at the 50,000-generation point in the journal Science. Entitled “Changing fitness effects of mutations through long-term bacterial evolution,” the journal’s editor noted –

“The number of beneficial mutations rapidly tailed off during long-term passage, with parallel changes in fitness cost and gene essentiality occurring across the lineages. The authors found nonessential genes that became essential and essential genes that became nonessential in all lineages.”

After decades of laboratory observation, an explanation to describe “how selection acts under nature” to drive evolution has yet to emerge.

However, the problem with finding evidence for selection processes is that laboratory models cannot replicate natural selection.

Field Observations in Water Fleas

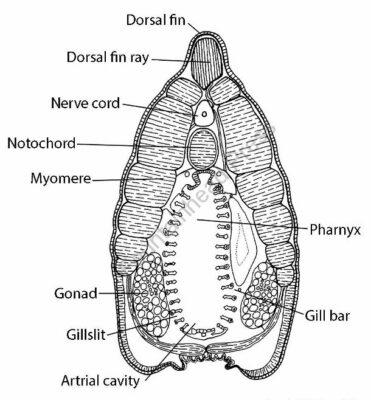

Water fleas, tiny crustaceans barely visible to the naked eye (pictured left), play a crucial role in aquatic ecosystems. They are found worldwide in freshwater habitats, from small temporary puddles to large lakes.

Water fleas, tiny crustaceans barely visible to the naked eye (pictured left), play a crucial role in aquatic ecosystems. They are found worldwide in freshwater habitats, from small temporary puddles to large lakes.

Following ingestion of organic matter, water fleas digest and metabolize the organic matter into usable energy for their prey’s consumption. Water fleas are in the middle of the food chain, a crucial link in the upward transfer of energy in aquatic ecosystems.

Without the water flea, Earth’s freshwater systems would be murky, algae‑dominated, low‑oxygen systems, undermining the diversity of Earth’s biosphere. Nature has selectively preserved the water flea throughout Earth’s history of dramatic ecosystem changes.

The water flea is one of the greatest stabilizers of Earth’s freshwater biosphere. Roughly 450 species are considered water fleas. The water flea, Daphnia pulex (pictured above), was the first to have its genome sequenced.

D. pulex, found throughout the fresh waters of the Americas, Europe, and Australia, has emerged as a model for studying the interplay between selection, genotype, and phenotype—natural selection in action. Adapting to ecosystem changes is crucial for preserving all forms of life.

Adapting to ecosystem changes is crucial for preserving all forms of life.

Change in phenotype within a generation is known as phenotypic plasticity. D. pulex has selective phenotypic plasticity cycles on two biological levels, defense and reproduction. Defensively, the flea can alter its neck morphology and can shift from sexual to asexual reproduction.

Water fleas are easy prey. For its defense, they can morph their dorsal necks (pictured right) into “neck teeth.” Observing these phenotypic plasticity changes offers a live model for studying “how selection acts” in nature.

“Neck Teeth” Observations

D. pulex selectively develops a strange neck morphological protective defense (pictured left) against its predators. The on-demand development of dorsal fin “neck teeth” is one of nature’s most interesting selective processes.

D. pulex selectively develops a strange neck morphological protective defense (pictured left) against its predators. The on-demand development of dorsal fin “neck teeth” is one of nature’s most interesting selective processes.

The morphological changes begin once the water flea detects chemical clues released by its predators. Dorthe Becker, a professor at the University of Sheffield, GB, recently completed a study of the phylogenetic plasticity of the water flea’s anti-predator defenses.

Their report, “Adaptive phenotypic plasticity is under stabilizing selection in Daphnia,” was published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution (2022), explains the study’s purpose –

“Little is known about the evolutionary forces that shape genetic variation of plasticity within populations.”

The study aimed to assess the type of evolutionary selection acting on the water flea, stabilizing or diversifying. While stabilizing is conservative, diversifying selection drives evolution. Becker (pictured right) notes –

The study aimed to assess the type of evolutionary selection acting on the water flea, stabilizing or diversifying. While stabilizing is conservative, diversifying selection drives evolution. Becker (pictured right) notes –

“Here, we address this issue by assessing the evolutionary forces that shape genetic variation in antipredator developmental plasticity of Daphnia pulex.”

However, stabilizing selection, as the paper’s title indicates, is an adaptive conservation process rather than an evolutionary speciation process. Because Becker’s evidence demonstrates a conservation process, it does not explain how selection operates in nature as a process of speciation.

As one approach closes, another approach opens.

Genetic Selection Coefficient

Michael Lynch, director of the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University, published a team survey of the 10-year dataset on the genome of the water flea population. Their report, “The genome-wide signature of short-term temporal selection,” was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS) in July 2024.

In the survey, Lynch found “little [genetic] evidence of positive covariance of selection across time.” The selection coefficient is a quantitative measure of genotype, a quantitative estimate of diversity. Lynch concluding –

“Most nucleotide sites experience fluctuating selection with mean selection coefficients near zero… These results raise challenges for the conventional interpretation of measures of nucleotide diversity and divergence as measures of random genetic drift and intensities of selection.”

The exchange of alleles over ten years did not produce changes in the flea’s genotype. With the findings, science writer Richard Harth (pictured right) took the high road in the article “Study challenges traditional views of evolution” –

writer Richard Harth (pictured right) took the high road in the article “Study challenges traditional views of evolution” –

“The study shows that evolution is more dynamic and complex than previously appreciated.”

Selection is nature’s conservation mechanism, but not a scientifically valid mechanism of speciation, as evolutionary scientists once expected. Without a scientifically valid mechanism for speciation, Darwin’s Origin of Species theory is once again in crisis.

While selection is a scientifically valid adaptive microevolutionary process, it is not a scientifically valid mechanism for macroevolutionary speciation.

Genesis

Commenting on the Genesis account of creation in The Origin of Species, Darwin (pictured left) concluded –

Commenting on the Genesis account of creation in The Origin of Species, Darwin (pictured left) concluded –

“On the ordinary view of the independent creation of each being, we can only say that so it is… but this is not a scientific explanation.”

After nearly 200 years of investigation, Darwin’s conclusion about the Genesis account mirrors the modern scientists’ view of Darwin’s theory –

“[It] is not a scientific explanation.”

Natural selection, a natural explanation for the origin of Earth’s biosphere, remains beyond the reach of scientific validation.

As a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization, and regarded as a founder of the germ theory of diseases, Louis Pasteur declared –

As a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization, and regarded as a founder of the germ theory of diseases, Louis Pasteur declared –

“A bit of science distances one from God, but much science nears one to Him… The more I study nature, the more I stand amazed at the work of the Creator.”

Selection, Third Principle of Natural Selection is a Theory and Consensus article.

More

Natural selection’s five principles, coined as an acronym and causal sequence, are V.I.S.T.A –

Darwin Then and Now is an educational resource on the intersection of evolution and science, highlighting the ongoing challenges to the theory of evolution.

Move On

Explore how to understand twenty-first-century concepts of evolution further using the following links –

-

- The Understanding Evolution category showcases how varying historical study approaches to evolution have led to varying conclusions. Subcategories include –

- Studying Evolution explains how key evolution terms and concepts have changed since the 1958 publication of The Origin of Species.

- What is Science explains Charles Darwin’s approach to science and how modern science approaches can be applied for different investigative purposes.

- Evolution and Science feature study articles on how scientific evidence influences the current understanding of evolution.

- Theory and Consensus feature articles on the historical timelines of the theory and Natural Selection.

- The Biography of Charles Darwin category showcases relevant aspects of his life.

- The Glossary defines terms used in studying the theory of biological evolution.

- The Understanding Evolution category showcases how varying historical study approaches to evolution have led to varying conclusions. Subcategories include –